Volts/Catalyst pod crossover: the biggest questions in clean energy

In this episode, I chat with Catalyst host Shayle Kann about the most pressing unresolved questions in the clean energy world today. We explore whether data center gigantism will break the grid, if the smart home revolution is destined for platform enshittification, whether billionaires should start testing solar geoengineering, and more.

(PDF transcript)

(Active transcript)

Text transcript:

David Roberts

Greetings, salutations. Konnichiwa. Aloha. This is Volts for February 25, 2026, “Volts Catalyst pod crossover — the biggest questions in clean energy.” I’m your host, David Roberts.

Back in November 2023, I did a crossover episode with the podcast Catalyst, hosted by cleantech investor and analyst Shayle Kann. Catalyst covers many of the same issues as Volts, with an even tighter focus on technology, business models, and markets. It’s been a while, so I thought it would be fun to do another one.

In our previous crossover, Shayle and I shared our respective lists of the most overhyped and underhyped technologies and trends in clean energy.

This time around, I thought it would be fun for each of us to bring a short list of the biggest open questions in the world of clean energy — specifically, questions we think might plausibly be answered in the next five to ten years. (That proviso made this undertaking more difficult than you might think!)

We discuss self-driving cars, the possible enshittification of home electrification technology, data centers (of course), and much more. This was a hoot — I hope you enjoy it.

Shayle Kann

David, nice to be back with you.

David Roberts

Awesome! Glad to be doing this again.

Shayle Kann

We gave ourselves a prompt here, which is that each of us has come prepared with three questions we are eager to see answered in the next five to ten years. I assume we both came with backups as well in case we overlap. I don’t think we will. I bet we are not going to overlap.

David Roberts

I tried not to overlap with you. I think we will. It’ll be funny if we both tried hard that we’re going to leave some very obvious questions on the table.

Shayle Kann

We probably will. I didn’t try to go super esoteric, but I at least tried.

David Roberts

I tried to get medium esoteric. We’ll see. You want me to go first?

Shayle Kann

Yeah, you go first.

David Roberts

Just to review for listeners, the prompt here is important questions facing the clean energy world that you might reasonably think will get some kind of answer in the next five to ten years. That turned out to be really interesting, really difficult, because I kept thinking of questions that I was thinking, “Will we really know in ten years?” There are lots of big questions where I don’t think we’ll really know until twenty or thirty years out. That was interesting as a way of bracketing my thinking about this.

Long story short, my first one is: self-driving cars are here, which is puzzling in itself since there was all this chatter and talk for years in anticipation of their arrival, and then they arrived and nobody talks about it. They’re operating in several cities now and nobody talks about it. It’s a little weird. But there are lots of really interesting questions about the macro effects of self-driving vehicles that I think we will get answers to pretty soon.

Now that San Francisco has been doing it a while and it seems to be working, I think Seattle’s starting a pilot. There are pilots starting in a bunch of cities. We’re very close to widespread adoption, and then we’ll start to get answers to some of these questions.

The fear that I have — that I think a lot of climate people have, greenies have — is that making it easier to take a car around is going to result in a lot more people taking a lot more cars around. Even though people might not necessarily own their own vehicle, even if they’re shared vehicles, the level of use of cars is going to rise sharply when it becomes so easy and convenient, which will translate mathematically into greater congestion. You could see deaths going down, as I think we’re already seeing in San Francisco. You could see noise going down if they’re all electric. You could see pollution going down if they’re all electric.

But on the core issue of urbanism, the fear is that they are going to work against density. They are going to make it easier to live far out. They are going to make it easier to commute. You are not going to dread an hour-long commute if you can just chill and read and tap on your phone or watch a TV show or something.

That’s just going to make it a lot easier to decide to live an hour outside of town. I think within five to ten years we will at least see cities where these things become ubiquitous. At the very least, we’ll have directional answers to some of these things. I’m very curious, Shayle, from your perspective, what your level of anticipation versus dread is — now that it’s here, is it just not that big of a deal either way? I’m curious what your disposition is on self-driving cars.

Shayle Kann

Good question. Many things to say about it. Let me offer you a few bits of exposition first. I live in the Bay Area, as I think you know. I don’t live in San Francisco, but I live outside the city and I’ve —

David Roberts

You’ve taken —

Shayle Kann

Of course, I Waymo. Regularly. Yeah, of course. And you’re correct that it’s just not a thing in San Francisco anymore. Not a thing in the sense that one out of every three cars in the city is a Waymo, and that’s just how it is. It’s become pretty normalized to anybody who’s not a tourist. I agree with you, it’s coming everywhere. I think five to ten years is the right time frame for this.

My other tidbit for you: I have a four-year-old son and I’ve been making bets about his future with anybody who wants to take them with me since he was born. One of the bets is that he will never drive a car, he’ll never get a driver’s license. He’s growing up in suburban Bay Area, California, so take that into account because this is a specific bet to my son. But I think twelve years from now, when it would be time for him to get his driver’s license — oh yeah, he’s not going to need to. Already lots of kids are just Ubering around.

That said, with your question, it’s interesting the framing of it to me because I had anticipated you were going to raise a climate concern, which you are not. You are saying, because the benchmark is a second order.

David Roberts

I think urbanism and density are climate-related. If you lose density, even if the cars aren’t polluting, you’re still going to get greater pollution and greater impact. There are second-order climate effects.

Shayle Kann

Probably, but I would bet — I don’t have data on this — but I would bet that those effects... One of the main reasons why density is lower emissions per capita is transportation. That’s a big part of it. If it is true, the benefit of self-driving vehicles from a climate perspective is that it makes a lot more sense for them to be electric. The utilization pattern —

David Roberts

They’re all Waymos, they’re all electric, all the extant self-driving cars on the road are electric today.

Shayle Kann

They’re pure EVs. It just makes more sense. You drive high utilization, you pay back the added CapEx of the EV much faster. It’s better for a bunch of reasons. If you assume that our self-driving future accelerates vehicle electrification, then to a first order, from a climate perspective, it’s not inherently a bad thing. That would be weighed against your question, which is: will there be more vehicle miles traveled total?

David Roberts

Yes.

Shayle Kann

Those weigh against each other to some extent. But it’s not obvious to me that a transition to autonomous vehicles is bad. From a climate perspective, it might even be good.

David Roberts

I would not have the arrogance to put my flag on either side of that. I think we just genuinely don’t know. I think that’s right — that it’s going to eliminate a huge chunk of emissions. The question is all these second-order effects and how you even really trace them. But I do think that continuing to sprawl outwards is bad for a number of reasons extraneous to climate.

Shayle Kann

I don’t have an opinion on that. I’m not an urbanist, I guess I would say in that way. I don’t have strong opinions on whether adding more sprawl is bad. I could see it happening. I have a friend who is a long-term real estate investor who is amassing a portfolio of land in the exurbs of certain cities under a multi-decade bet of exactly what you are describing. I could see that happening. I just don’t inherently see it as a bad thing.

David Roberts

The question of whether exurbs are bad or not is a large question that we don’t have time to address here. I think this would reinforce the worries of the urbanists, which is that they see the tech guys pushing this and I don’t see any sign from the tech guys that the tech guys care about this. They drive themselves everywhere. They don’t live in walkable places. The physical form of Silicon Valley is so gross. It’s so gross and deadening. But I guess that’s all they know anyway. At the very least, we’ll be able to see if that sprawl happens and then we’ll be able to answer the question of whether we like the effects or not.

Shayle Kann

What we can measure to answer your question of what we know in five to ten years is: in the cities where there is high proliferation of autonomous vehicles — San Francisco and five to ten years from now, probably a bunch of other cities — will total VMT have gone up over that period?

David Roberts

Yes, because they are pushing in the other direction in California with policy. They are trying to restrain sprawl with a lot of other policies. How will that balance out? Or it might even be more interesting to see what would happen to a city like Cleveland or whatever if they get a bunch of AVs, because they do not have a strong overlay of other laws restraining them. It would be more of a clean experiment. We’ll probably see.

Shayle Kann

Phoenix has been the test bed for autonomous vehicles.

David Roberts

Are they a thing there now?

Shayle Kann

Yeah, that’s where a lot of the early testing was, in some ways because it’s obvious — Phoenix is a simple grid, it’s not hilly, the weather’s good. It’s the opposite of San Francisco. San Francisco was trial by fire for Waymo. But Phoenix is —

David Roberts

Phoenix is already sprawling like crazy. A little tricky to separate the signal from the noise, but yeah.

Shayle Kann

Can I give you my first question?

David Roberts

Take your first one.

Shayle Kann

The obvious question that I’m going to ask — I’ll try to ask a different version of the obvious question — is: how hot will data center fever get and will it break in the next five to ten years? Five to ten years is probably the right timeframe to ask that question.

David Roberts

I was wondering about that.

Shayle Kann

You could argue it could be sooner, but who knows. Within the next ten years, we will see some directional thing here. Instead of asking the question of how hot will the data center fever get and will it break, I’ll ask a different question, which is a second-order effect of that: how much large load goes off grid in the next five to ten years?

To walk through the chain of logic, the going assumption right now is that there is so much demand for new data center capacity that we are going to be bursting at the seams on the grid. In any market that has demand for data centers, we’re going to tap out everything we could possibly do on the grid, so much so that maybe we need to go to space. But I think before we go to space in significant volume, there would be a good chance we would go off grid. We’ve never seen a lot of large industrial loads go off grid apart from mining and things like that. We’re starting to see glimmers of it right now in data center world.

David Roberts

Are we not seeing — didn’t someone just propose or pass a law that said you have to —

Shayle Kann

Josh Hawley in the Senate and somebody else, I think, introduced a bill that would essentially mandate data centers to go off-grid. My presumption is that doesn’t pass.

David Roberts

I’ve said several times, there’s a world of difference between bringing some generation and bringing enough generation to cover yourself if you go off grid entirely. That’s a very — we’re talking about hundreds of megawatts.

Shayle Kann

Yeah. What’s happening now? To be clear, there’s an enormous amount of bring-your-own-generation that’s happening. No question about that one. That’s an answered question. The question that has not been answered is — there’s also an enormous number of projects that are saying, “Okay, we’ll do bridge power. We’re going to be off grid until we get the grid connection.” That’s going to be a year, three years, five years, whatever it might be. I’m saying forget the grid. How many large loads will just be fully off grid with no intent to get a grid connection? Will that happen in significant volume? That is an interesting question.

David Roberts

It is interesting. My gut instinct strongly says no. The arguments for a grid — a grid is handy. Grids are extremely useful. A lot of policy discussion right now is being forced into weird shapes because it’s trying to work around the fact that we can’t do the obvious thing, which is just build more grid. That would solve all the problems. That’s what everybody wants. It’s what everybody needs beyond data centers, even for the future, period. We just need to do that. We’re torn between trying to make that happen and then trying to weasel our way around it. I guess that’s how that works.

Shayle Kann

You’re making the case. The fact that we’re not solving that — you could make a case that we will solve it, but if we don’t solve it, then what happens?

David Roberts

That’s an even broader question. I could imagine a story where our social and political dysfunction, our inability to build quickly, forces these weird around-the-edges solutions that end up growing and developing in ways that we can’t anticipate now and bring new things into the world. It will spawn invention and innovation. Even though if you had your druthers, you would not choose this situation, I do think it will force some very creative thinking.

Shayle Kann

To me, it really comes down to this question: is it really true that for an extended period of time into the future we are going to have dramatically more demand for data center capacity than we have ability to serve it on the grid, with money attached to that demand that is willing to take some risks that maybe hyperscalers would not have taken in the past, for example?

If those things are true, then it is inevitable to me that some amount of it — and I don’t know how much — is going to take the one risk that is introduced by not being on the grid, which is largely reliability. You don’t have as many nines of reliability unless you really overbuild a bunch of on-site stuff. What you get in exchange is you get unleashed from a siting perspective. Imagine how easy it is to site something if you remove the constraint of the transmission.

David Roberts

But you are, I take it, imagining very large gas plants.

Shayle Kann

I’m not imagining a lot of them. I’m watching them get built right now.

David Roberts

I haven’t accommodated myself to that yet. I don’t want that to happen.

Shayle Kann

But that’s happening.

David Roberts

I know.

Shayle Kann

Maybe not the off-grid version. By the way, it doesn’t inherently have to be gas. There’s a good study that Paces and Scale Microgrids put out a while ago that was, “Can you run at high utilization a data center fully off grid with mostly solar and storage?”

You generally need a little bit of dispatchable generation. You mix your things together and end up with some gas. But it is just a microgrid.

David Roberts

It’s the same question that faces any microgrid. You can do X amount with variable and you need some marginal amount of dispatchable to firm up.

Shayle Kann

Or batteries.

David Roberts

You need more batteries. That’s what I want to see. That’s what I think could more straightforwardly substitute for natural gas — more and bigger. Because half of your shows and my shows are about this now. This question, the way you ask it, is also tied up intimately with a bunch of other super fascinating questions.

Are data centers going to continue evolving in the direction of gigantism, or is there a serious prospect for more distributed, more modular, more grid-edge data centers? That’s a super interesting question. Then there’s the bigger question of: will there be radical efficiencies in chip design that mean we don’t need the sheer quantity we think now, or will the bubble pop?

The question of how many data centers there will be — lots of people want to know the answer to that question, not just the power people and the grid people. How do you think about — and we can move on to the next one — this is something I try to think about how I talk about what I want to say.

Here’s another note I would put: before they take the extraordinary step of trying to build their own — if you’ve got a gigawatt data center and you’re trying to go off grid, you’re basically building a pretty large grid. You’re building a city’s worth of electrical infrastructure. It’s a pretty extreme step. I would like to see them, because they can’t get nuclear plants quickly or coal plants quickly or natural gas plants quickly, get serious about exploiting distributed capacity. I think that’s faster and cheaper than on-site generation if we can get the financial and institutional arrangements lined up the right way.

Shayle Kann

The whole scenario here is a yes/and. The presumption is there will be enough demand. We’re going to tap out every available possibility. We’re going to get more on existing lines to do some distributed capacity aggregation — all these things are starting to happen. I think they’re going to continue to happen. Yet in the absence of building out an entirely new transmission system on top of our existing transmission system, we’re going to hit a ceiling. Or at least we’re going to hit a ceiling from a time-to-power perspective.

David Roberts

The fact that all these forecasts are saying we’re going to build more data centers than we could conceivably power is good evidence that it’s not going to happen. I’m very skeptical. I would ask you the central question: do you think demand is going to get even close to the higher-end projections, or are you a deflationist on this?

Shayle Kann

I don’t think I am smart enough to know the answer to that question. I don’t think anybody really knows the answer to that question. I do think there is pretty universal agreement among people who are building these models that we’re going to need — to your point on, “Will it shift to the edge?” Yes, inference might. That’s an open question. There is going to be for some period of time in the future demand for more and more powerful models. Those require the centralized, big-ass data centers. We are already starting to have a harder time finding sites on the grid to power those in the time period that people want.

I think there is going to be some period of time where we are bursting at the seams from an electricity perspective. I don’t know how long it lasts. I don’t know whether it gets to the point where Elon wants to put 100 gigawatts a year of orbital data centers in space.

David Roberts

Do you think there are going to be space-based data centers? You did a pod on it, didn’t you?

Shayle Kann

We’ve talked about it a bunch. I’m doing more on it. I’ve spent a lot of time now understanding the economics. To me, the answer to that question is the answer to the question you asked me. Because I think that orbital data — Elon says he thinks that they will be the cheapest way to get new compute in three to five years. I do not think that is possible, not in that time period.

David Roberts

He says a lot of things.

Shayle Kann

If you think that there is going to be this insatiable appetite and we’re going to need to scale to hundreds of gigawatts a year and we are not going to have the ability to do that on the grid, then the interesting question is: your options are off grid or off world. Then it’s a different comparison and it’s interesting to think about. We should get off of the data center thing.

David Roberts

The final thing I would say about it, and this is the note I wanted to say earlier: when I talk to people who are — as you know, there’s a very loud constituency to the left that hates data centers, hates AI, hates the whole discussion — all I would say as a final note is even if you think that short-term data center demand is radically overstated and that these data centers are not going to end up with as many as currently forecast, it is nonetheless the case that we’re electrifying transportation and we’re electrifying heat and cooling and we’re electrifying industry, and we’re just going to need lots, lots, lots more electricity and a much stronger, better grid in the future, regardless of what happens with data centers. I just think that should be — I don’t want those two questions to start to be conflated in people’s minds.

Shayle Kann

Put a pin in that when we get back to my next question.

David Roberts

Interesting. I’m on my second. Is that where we are? This is another one that I brought because I don’t think tech people are thinking about it enough or taking it seriously.

Shayle Kann

I love that I represent tech people.

David Roberts

I’m sorry. I’ve drafted you into this unenviable spokesperson job. Here’s my thought. You and I know that the long-term evolution is that everything that is plugged in is going to become a resource eventually. The notion of DERs as a distinct category is just going to fade away because eventually everything that plugs in is going to be managed by software that is in communication with larger grids. That is just going to become the default on some time horizon. We can talk about how fast we think that is going to happen, but it is going to happen.

What that means is that a lot of things that we have held as distinct from software are going to become software — like driving in cars and living in homes. On the one hand, I think there is immense potential there. As I have done a kajillion podcasts on, I think it is going to be extraordinary. We can have a much stronger grid. We are going to make each electron go further. We are going to utilize our grid better. We are going to have a more small-d democratic grid, etc.

For the most part, I love this trend and I’m very hopeful for it — the internetification of the grid. But — capital B — when I think about software as it exists today, it’s awful. The situation is awful. I’m not far from the only person saying this. It feels these days like the tech sector, which is basically the software sector in public, is exploitative, out of touch, getting increasingly deranged, talking about their bunkers on their islands, talking about the Antichrist, all fucked up on ketamine, just off in la la land.

Software feels exploitative these days almost everywhere you encounter it. Enshittification. I did a whole pod on enshittification. Platforms enter what seems like this inexorable cycle where they enshittify, and this trend of your house and your car becoming software — I don’t see enough people raising red flags, saying, “Do we want intrusive ad-based, ad-supported, subscription nagging, different tiers, real-time variable pricing, all these exploitative things that we’re running into? Do we want that in our cars and in our homes? Are we going to end up with enshittified homes?”

Is the promise of coordinated distributed energy going to manifest in reality as just another chapter of chintzy, exploitative, enshittified software that ends up exploiting the people who get stuck with it? I worry about that and I don’t hear hardly anybody else worrying about that. Do you worry about that?

Shayle Kann

Do you have a Nest thermostat?

David Roberts

I do not. My house is so analog and primitive, my current house.

Shayle Kann

If I think of what are the things in the home that tie to electricity that have been software-ified, thermostats are the obvious one to me via Nest and Ecobee and other companies like that. People who have EVs have an EV charger and then they have a software platform that goes on top of that. There are EV owners. I drive an EV9. I’m sure you’re an EV driver, a Kia.

David Roberts

The big one. The big one is nice.

Shayle Kann

The big one is super nice. It’s the best. There’s the vehicle, there’s the thermostat. If you want to go newer age, I am an owner of a Quilt, which is a —

David Roberts

Oh, you got one of those?

Shayle Kann

— version of a heat pump. EIP is an investor. I was customer number seven of Quilt.

David Roberts

Do you have one of the newer — because didn’t they just refresh the look of their wall units? I feel they’ve always — am I making that up? Super cool looking.

Shayle Kann

But it is what you’re saying. It’s software-ification. It’s got an app. It’s much more controllable. My personal experience with all those things is that they’re better. I haven’t heard anybody saying, “Nest enshittified the thermostat,” or, “The Tesla app enshittifies my EV charging or my charging experience.”

David Roberts

If you’re familiar with Cory’s work, you know that always stage one on the platforms is that they’re good to users and that they offer genuine value to users. That is step one of this process — you attract the users with genuine value and then over time work to make leaving the platform difficult. When people are locked in, that’s when you start exploiting them. I will agree that all of this is nascent and new and barely there that we’re just on the front end of this. A lot of this is speculative, but it sure seems like that is the direction everything travels.

One way I think about this — and this is probably something you have heard me talk about before — one thing that I am just waiting for is if the self-driving cars become ubiquitous, what is to stop them from offering a free tier that is ad-supported, which everybody then chooses because nobody wants to pay up front? Then that is one more little area of our lives where we are constantly beset with customized advertising. That is one way.

Shayle Kann

Maybe I’m going to own my tech bro-ness. If I decide to get free rides around in my future Waymo or whatever it is in exchange for being served ads, that’s a trade I make deliberately and happily. I get free rides and that’s worth it to me. I don’t see that as being inherently a bad thing. There are challenges to the ad ecosystem.

David Roberts

But you recognize enshittification as a thing that happens on other platforms? Or are you skeptical more broadly about Cory’s work?

Shayle Kann

I don’t know Cory’s work, let me preface with that, but I think I see what you’re talking about and I can come up with examples of it. I don’t know that I see it as the inexorable direction of travel when things become software-y, particularly as it pertains to me.

David Roberts

It’s less software-y than platform-y. It’s the platforms. This is why I want — if your water heater is signed up to some VPP and your thermostat’s signed up to another one, they’re both on different platforms — I want interoperability and I want the ability to move from one platform to the other without penalty. I don’t want lock-in. That’s what leads to platform enshittification — lock-in. I think we could avoid a lot of that up front if we just went in with some clear privacy laws and some clear rules and regulations about interoperability and transparency.

Shayle Kann

I don’t disagree with that. That’s a pretty innocuous statement to make to me. At the high level, the things that I think about that are in our homes — I’ll just focus on the home for now — that are hopefully going to be transformed such that, as you said, eventually all of them are software-enabled, interact with the grid, enable them to be responsive to the needs of the grid, but also have more capabilities for the customer. When I think about them one by one and what I think the future of those things is going to be, I generally think it will be better.

Certainly the ones that I can think of today that have already started to be that way feel better to me. I can see how it could go off the rails — I have watched Idiocracy — but where we stand today, I don’t see evidence of that.

David Roberts

It’s early enough now that I don’t have a lot of concrete examples to hang this on. Mostly it is just a generalized fear. But I look at the exploitation and the crappiness around us in every other area, and I just don’t want that coming into my home and hearth.

Shayle Kann

Fair enough. Can I come back to the last statement you made in the last question to ask my next question?

David Roberts

Segue me.

Shayle Kann

You said you wanted to be careful to separate out the “we need to improve the grid because we’re going to be electrifying all these other loads” from the “some people just don’t like data centers” thing. I agree with that generally. But here’s my concerning question. I think we may or may not have fully answered it in the next five to ten years, but we will know the direction of travel, which is: is electrification dead, or will electrification be dead as a pathway for industrial emissions reduction?

David Roberts

Just to walk through the logic here — will it be dead when, for what reason?

Shayle Kann

Will it appear dead over the next five to ten years? The reason is that you have two things happening in my mind right now that are pushing against it. For a long time I’ve always said, to a first order, the simplest way to solve climate change is clean up electricity, electrify everything that you possibly can, and then go fill in all the pieces of the stuff that you just can’t possibly electrify. That implies electrifying a big portion of heavy industry, for example.

If you are trying to electrify something in heavy industry right now, or even something that hasn’t been electrified but is already electrified — take an aluminum smelter, for example. You just want to build a new aluminum smelter, which uses hundreds of megawatts of electricity. You can’t find a site because every site is being taken up by a data center, and your prices are higher and you’re sensitive to electricity prices.

David Roberts

I see where you’re going with this.

Shayle Kann

The premise of industrial electrification is you get cheaper operating costs because it is electrified. You’re going to get probably higher capital costs. This is the trade with everything that you electrify, and then you save money over time because it’s much more efficient. That is a function of the spark spread — it’s the difference between the price of electricity and the price of natural gas.

David Roberts

And also less waste and less regulatory compliance.

Shayle Kann

Easier to permit. But in a world where you have a really hard time siting because there are not that many places to put 100-megawatt, multi-hundred-megawatt loads, and where there is inflationary price pressure on electricity, which there certainly is today, that value proposition is eroded. I wonder what happens.

David Roberts

More broadly, both of us wanting to electrify everything, I think naturally leads to both of us being daunted at the fact that electricity prices are high and rising. Those are obviously at odds on every level — industry particularly, but also residential, also transportation, also everything else. Which gets us to the question of the day, the political question of the decade really, which is how you bring down electricity prices while continuing to rapidly and aggressively electrify.

Another question I had about industry that I almost brought — I’ll just throw in here — does it in fact start electrifying in this circumstance where electricity is expensive and data centers are bullying them out of the way and grabbing all the electricity? Another question that I didn’t bring today because it’s definitely a twenty-year-plus question is: when we say electrify everything, do we mean industry too?

By that I mean, how much faith do we have in electrochemistry to replace — right now you can make steel with zero emissions electrochemically, it is just wildly expensive. Same thing with concrete — you can do it electrochemically with zero emissions, it is just much more expensive. Is electrochemistry going to come along fast enough that we could really electrify everything? The reason I did not bring that question along is that it is definitely a twenty-plus year question.

But I think/hope, let’s call it a 50/50 split — that in the long, long term I really think we’re going to electrify everything. I’m an absolutist. Once you’ve built a single unified system that is providing power to 98% of stuff, whatever that 2% is, the benefits of just being able to hook into that system are so immense that it’s just going to overcome whatever barriers there are.

Shayle Kann

I think I agree with you in the long term. Now we’re at 25% in the US, 25% of final energy consumption is electricity. 75% is not — worth remembering that.

David Roberts

It’s a long way to go.

Shayle Kann

For a long time, I think people who were seeking to electrify, particularly industry, rested on this belief that the marginal price of electricity was plummeting towards zero.

David Roberts

Electrochemistry in particular very much depends on copious, cheap electricity.

Shayle Kann

That is not the world we’re living in right now. It’s probably not the world we’re going to live in for the next few years. Now it may turn back — this could be cyclical and five years from now it will turn back. But the current state of affairs is electricity prices are going up, not down.

David Roberts

One thing that might be answered in the next ten years is: everybody’s freaked out about electricity prices now. The entire Democratic Party is seized with this. Will we be able to pass policies that reduce the price of electricity in an enduring way? Reform utilities, infrastructural permitting reform, stuff like that? Will we be able to do that? That’s an open question.

Shayle Kann

I don’t know. Five to ten years is an interesting time frame under which to think about this question. But I can tell you, I think over the next three years, electricity prices are probably going up, not down.

David Roberts

That’s going to make that value proposition harder, and that’s bad. I think everybody in our world really needs to uprate the question of making electricity cheaper. It really is a pivot on which everything else turns. That alone could screw us, could screw everything else if we can’t do it.

Shayle Kann

I agree with you. To your point, I think a glimmer of hope here is that there is alignment. Everybody — the word “affordability” is going to be the key word in many circles for the next couple of years. It has become, as you said, a political hot-button thing. It’s the word of the day among utilities, among data center companies, and among everybody else. Affordability is the thing.

David Roberts

We are in the lucky position that the kinds of energy we favor are the cheap ones. You can take climate out of the picture — there’s still going to be a lot of moneyed interests pushing for lots more clean energy and batteries for reasons having nothing to do with the environment. I’m on my third one, yes?

I think so.

My third and final one. This is something I’ve been thinking about. Here’s how I’d phrase it: is J. B. Straubel going to turn out to be as or more significant to the long-term fortunes of clean energy than Elon Musk?

By which I mean, J. B. Straubel set up this big battery recycling company, Redwood. Arguably before there were many batteries.

Shayle Kann

Enough batteries.

David Roberts

They were scrambling to collect old vacuum cleaner batteries and double A’s and stuff just to keep going long enough for the batteries to show up. But now I think we’re just on the cusp of the first wave of used-up batteries coming in. The reason I raise all this is that there’s this whole question about critical minerals, about materials, and about who dominates supply chains.

Everybody in the world is freaked out because China dominates all the supply chains. They mine all the critical minerals, do all the processing, etc. We’re very dependent on them. There’s been a lot of talk about how the US can stand up a supply chain of its own. There’s been lots of talk about mining and stuff in the US, although not a ton of action.

I think we should start viewing electronics themselves, cleantech itself, as a source to mine. If we can capture those materials and reuse them effectively infinitely, then when you buy a solar panel from China, it is as though you are both buying a solar panel and mining a certain quantity of materials that will be available after the solar panel is dead.

Recycling is a source of critical minerals. It is a strategic source of critical minerals. If you take the growth numbers of EVs and solar panels and all the rest of it seriously, it’s going to be a very large source of minerals, a large source of raw materials. All of which just means that I think recycling is going to go from an environmental nice-to-have, which is how I think people are thinking about it now, to something like a national security — energy security imperative.

If you get your hands on some of these materials, it is absolutely in your interest to make sure that you keep recycling those materials through your economy forever. I think recycling in the next five to ten years is going to A) take off and B) become much, much more strategically important. Wonder whether you think so. Wonder whether you agree.

Shayle Kann

I do agree generally. It’s not just EV batteries either. Redwood is recycling EV batteries and a bunch of other old batteries and getting out of it the lithium, nickel, cobalt, stuff like that. We invested in a company called Cyclic Materials that’s doing recycling for rare earth elements. Rare earth elements are the least recycled critical mineral, which is crazy.

David Roberts

Out of coal piles?

Shayle Kann

No, not tailings or coal piles or anything like that.

David Roberts

I saw a different company doing that.

Shayle Kann

Motors and magnets and stuff like that. There are companies that are now doing solar panel recycling. I think that where I agree with you is I’m a recycling maximalist. We should recycle all this stuff. It has high value at end of life and we should take advantage of that value and that should mitigate the amount of new virgin mined stuff that we need in any category where we possibly can, particularly in those where there is a geopolitical reason that we want to have our own sovereign supply.

The only thing I would push back against is that the challenge — let’s just take battery recycling. If you believe that we are on a steep upward trajectory of demand for new batteries, then you’re forever going to be in a position where the amount of supply that you have to recycle is the amount of demand that there was ten years ago.

David Roberts

Not literally forever, but until you hit the top of the S curve.

Shayle Kann

That’s what I mean. Unless you think we’re already at the top of the S curve, which I don’t think either of us do, then it will matter some, but it is not a solution to our sovereign mineral supply problems.

David Roberts

My prediction would be that in ten years, maybe in twenty, a unit of critical minerals drawn from recycling will be cheaper than a unit mined. Eventually, I think it will end up being our primary and cheapest source of those.

Maybe you disagree, but I don’t think we’re ever really going to be in a position where we’re fully autarkic, where we fully have a contained and complete supply chain. Mostly this is just about having a little bit of a buffer. People need to start thinking of recycling like they think of mining — as a large and probably the cheapest source of those materials.

Shayle Kann

I agree with that. To the point on it should be cheaper — I’ll give you a specific example in the rare earth context. There are sixteen rare earth elements that are grouped together. We really only use four of them. If you’re doing virgin mining, you get this basket of all of them and you have to do this complicated separations process to get the stuff you want. If you’re doing recycling, you’re only getting the stuff we were using in the first place already. You’ve already cut out a bunch of expensive separation steps in the value chain. There are a bunch of reasons why fundamentally I think it should be cheaper.

David Roberts

There will be such an economic push on that that there will be tons of innovation and we’ll get something closer to an actual closed loop. Because this is like 50% of future sustainability. We focus so much on the energy part, but also the closed physical loop, the reducing physical waste and physical throughput, is the other half of the equation. Creating something like a closed loop of minerals.

The one thing that offsets that dynamic that you very accurately lay out — the demand is going up faster, so by definition, your recycling is behind your new demand — one force does slightly offset that, which is the lithium you get out of the old batteries will go farther in the new batteries than it went in the old batteries just because batteries are always constantly improving. You will get more. You won’t catch up to demand, but you’ll get more than that. It’s not fungible.

Shayle Kann

The place you want to end up in all these other critical minerals is where we are — maybe a little better than where we are today — in more mature supply chains, like aluminum, copper. Aluminum, we do recycle a lot of that stuff.

That doesn’t mean we don’t still need a lot more. It doesn’t solve your problem, but it’s meaningful. Can I do the last one?

David Roberts

Yes, last one.

Shayle Kann

Question to answer in the next five to ten years, maybe not next five to ten years, to be honest. Maybe this is a question that gets answered in twenty years, but nonetheless I’m curious: will we see a meaningful scaled geoengineering demo?

David Roberts

I thought you were going to say geothermal.

Shayle Kann

Geothermal — that better get answered in the next five.

David Roberts

That one I think will be — I think in ten years we’ll know whether geothermal is going to pay off the promise.

Shayle Kann

We’ll know. At least traditional is for sure. Traditional hydrothermal, probably EGS. Who knows about super hot rock. Anyway, I’m not asking about geothermal, I’m asking about geoengineering. Will we see somebody go do a big solar radiation management demo?

David Roberts

I have a solar radiation expert coming on the pod in a couple of weeks to talk about just this. I’m torn on this question. There are a bunch of cowboy jerk-offs in Silicon Valley doing this already. They’re doing little — I don’t know what counts as —

Shayle Kann

To defend my people in Silicon Valley, I would not say that. The group you are referring to is not of Silicon Valley.

David Roberts

That’s just one balloon at a time or whatever. I’m not super clear what they’re doing. I don’t know if that counts as a test at scale. I’m torn about this and curious what your thoughts are on the moral hazard side of things. Depending on what side of the bed I wake up on, I can take different sides of this argument.

On the one side — and this I suspect is your side and a lot of people’s side — this is pretty cheap. Somebody’s going to do it. Climate change is going to get so bad somebody’s going to do it. We might as well do it in a conscious, planned, controlled way.

The other side is, in a sense, the whole field is protected by being obscure and not a lot of people know about it. What happens if you start doing high-profile tests and experiments and make this a real thing? Suddenly then everybody around the world is going to be told, “Hey, you could, with like 150 bucks, go fiddle with the climate.”

Then you’ve got a whole Pandora’s box thing going because — this is the scary thing about solar radiation management — you could stand up and do a reasonably large-scale test on your own without a ton of money, arguably without being detected doing so by the world. The fact that no one’s doing that yet, I just think they don’t know they can yet. I don’t want them to find out. What do you think about that aspect, the moral hazard part of it?

Shayle Kann

It’s tricky. To fearmonger you a little bit more, I’m going to use a dirty word to you, I suspect, which is that a billionaire could probably get us half a degree C of cooling globally. That’s the crazy thing about SRM — the estimates, we don’t really know, we don’t exactly know efficacy, but the rough estimates, just to an order of magnitude, are that at least what I’ve seen, it might cost a couple billion dollars to deliver something like a half a degree of cooling. Half a degree centigrade of cooling.

David Roberts

But if you follow the literature, the cloud of uncertainties around all of this — unanticipated effects, second-order effects — things could go so horribly wrong. That is precisely the kind of question I don’t want random individual billionaires answering. This argues for really wrapping our heads around it and doing it explicitly just because somebody needs to wrap their hands around it and start controlling it.

Shayle Kann

It’s the thing where you want the equivalent of the International Atomic Energy Agency — you want the UN to take charge of this and say, “For the sake of the world, we need to explore this, but it should only be done in a coordinated fashion,” or something.

David Roberts

But think about the difficulty that nuclear arms regimes have had ferreting out and finding out whether a country is doing a nuclear program. A nuclear program is big and expensive and requires very specialized knowledge. It is very difficult to do that without being noticed, and people are pulling that off. I can’t imagine an international enforcement regime that could enforce this. It is easy to do. If a billionaire does it and another billionaire doesn’t like the way the billionaire does it and decides to undo it or do it a different way or redo it. Do we want billionaires getting the idea that they should be involved in this field?

Shayle Kann

I was going to trigger you with billionaires, but I don’t know. The problem is, I think the solution is not to put our heads in the sand, because the more we collectively put our heads in the sand about it, the more likely it is that that’s the way it gets developed, ultimately.

David Roberts

Trying to do it on purpose and with eyes wide open is the best we can do, but, boy, am I nervous about how that plays out. You can’t not do it. You can’t put a lid back on it. You can’t unknow what we know about it now. The only way out is through. We have three minutes left. You want to toss out one of your spares just to intrigue the audience? Just titillate an audience with a question we didn’t get to?

Shayle Kann

My spares weren’t great, actually.

David Roberts

I had some really good spares.

Shayle Kann

Hit me with some spares.

David Roberts

One of my spares I was surprised you didn’t bring up. I almost brought up: what’s going to happen with permissionless DERs?

Shayle Kann

I just did an episode.

David Roberts

I listened to it. I did one on Balcony Solar not long before that. People know this as Balcony Solar. It is any distributed generation or battery that you can plug in without getting permission from a utility or from anybody, really. You can just plug in.

Last I heard, 25 states had laws either proposed or announced to be proposed to legalize balcony solar. That’s half the country right there. That’s 25 states. That’s probably pretty soon, and I’m sure many more will follow in the wake. I’m fascinated by what effect it’s going to have. I think you and I probably agree that the net megawatts produced by this stuff is probably not going to be huge.

The question is: will the ability to put your hands on it and fiddle with it and play with it in a DIY way — Legos in your backyard — spark a subculture? Is that going to spark a lot more people to care and get involved and just be aware of solar? I’m curious how you think that’s going to play out.

Shayle Kann

Balcony solar punk? I don’t know. I need to learn more about Germany. I haven’t spent enough time understanding what’s a huge thing.

David Roberts

It’s a gigawatt. They got a gigawatt. I guess it’s not that small of a net amount. They have four million, something like that, systems installed from three years of it being legalized. Clearly, people like it. I’m curious what the distributed social effects will be of that. I know both of us will be translating.

My other backup, which I thought was good, but which you and I are probably not the people to discuss, is: China is in a state of overproduction of batteries and solar panels, which means they are selling solar panels to their neighbors at ludicrously low prices, which means countries — like Pakistan and Vietnam — are being flooded with cheap solar.

Pakistan went — I think it was like two or three years — 40% of its total load. Now it has imported solar panels equivalent to 40% of its total load. Give that another two, three years. We’re going to see what happens when a massive spontaneous upwelling of distributed solar energy meets rickety developing world grids.

How does that resolve itself? What happens when Pakistan has enough solar panels that it’s more than 100% of its total load? You’re going to get all these problems that grids get with lots of solar — balance and frequency management and inertia and all this stuff. But all of this is unplanned. The leaders of Pakistan did not arrange this. They didn’t have anything to do with it. The same is happening in Africa, it’s happening in Vietnam. I’m curious, what does the spontaneous unplanned profusion of solar at the ground level do to a country’s electricity system physically and also politically? That’s a very big change happening very rapidly. We have no idea yet what’s going to come out of it.

Shayle Kann

Great question. Not one we have time to answer. Let’s watch it.

David Roberts

We’ll leave you listeners to ponder what’s going to happen in Vietnam.

Shayle Kann

David, this was fun. Thanks for doing it again.

David Roberts

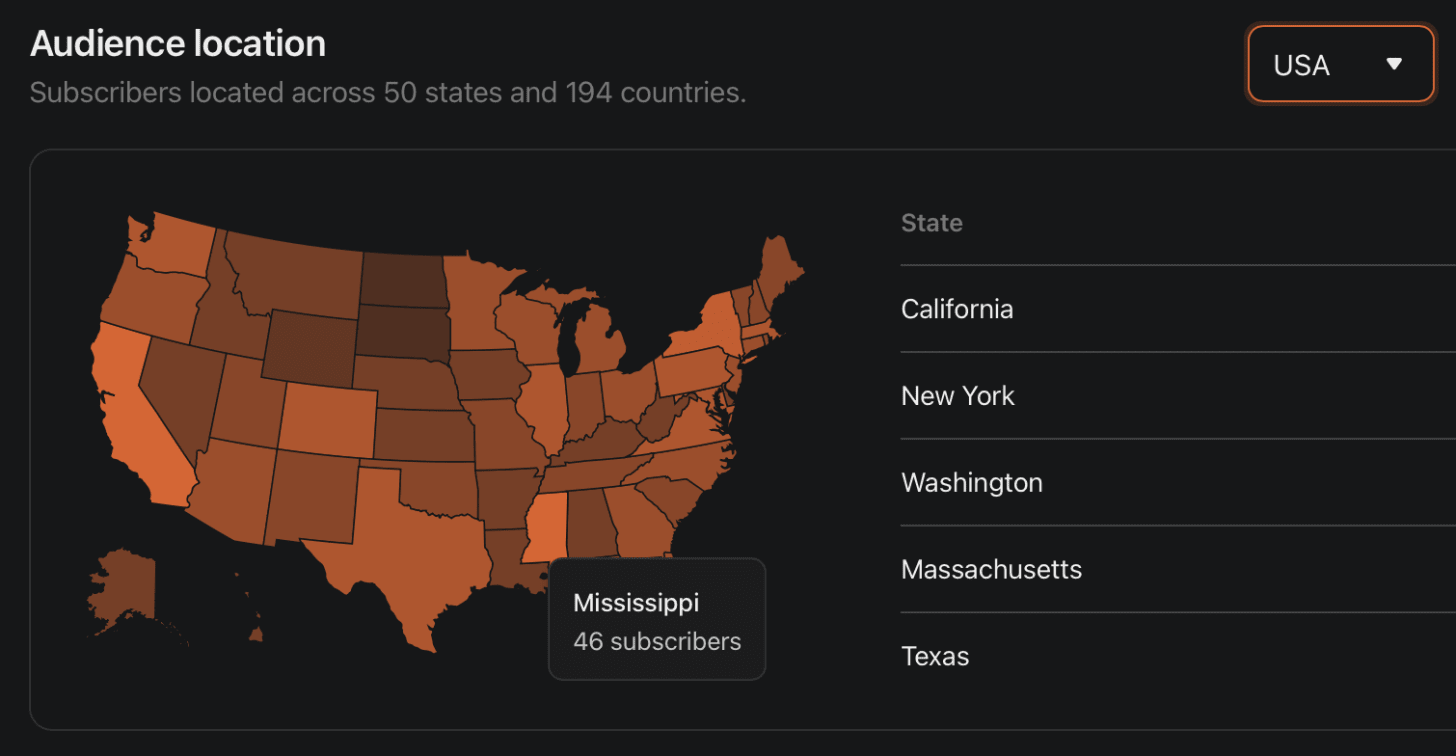

We’ll do it again next year. Thank you for listening to Volts. It takes a village to make this podcast work. Shout out, especially, to my super producer, Kyle McDonald, who makes me and my guests sound smart every week. And it is all supported entirely by listeners like you. So, if you value conversations like this, please consider joining our community of paid subscribers at volts.wtf. Or, leaving a nice review, or telling a friend about Volts. Or all three. Thanks so much, and I’ll see you next time.