Can fake meat help solve climate change?

Meat is responsible for roughly a fifth of climate change, the lion’s share of deforestation, 70% of our antibiotic use, and quite possibly the next pandemic — and consumption is going up every single year, with no end in sight. In this episode, Bruce Friedrich of the Good Food Institute joins me to argue that the only way out of this mess is better meat: plant-based and cultivated alternatives that can compete on price and taste, the way renewables now compete with fossil fuels.

(PDF transcript)

(Active transcript)

Text transcript:

David Roberts

Greetings, everyone. This is Volts for February 18, 2026: “Can fake meat help solve climate change?” I am your host, David Roberts.

When I recorded a pod about agriculture and climate change with author Mike Grunwald last year, we briefly touched on the outsized environmental footprint of meat production. In that conversation, I expressed a degree of resignation about the meat problem. I didn’t see any realistic solution, which is one reason I’ve never particularly relished talking about it.

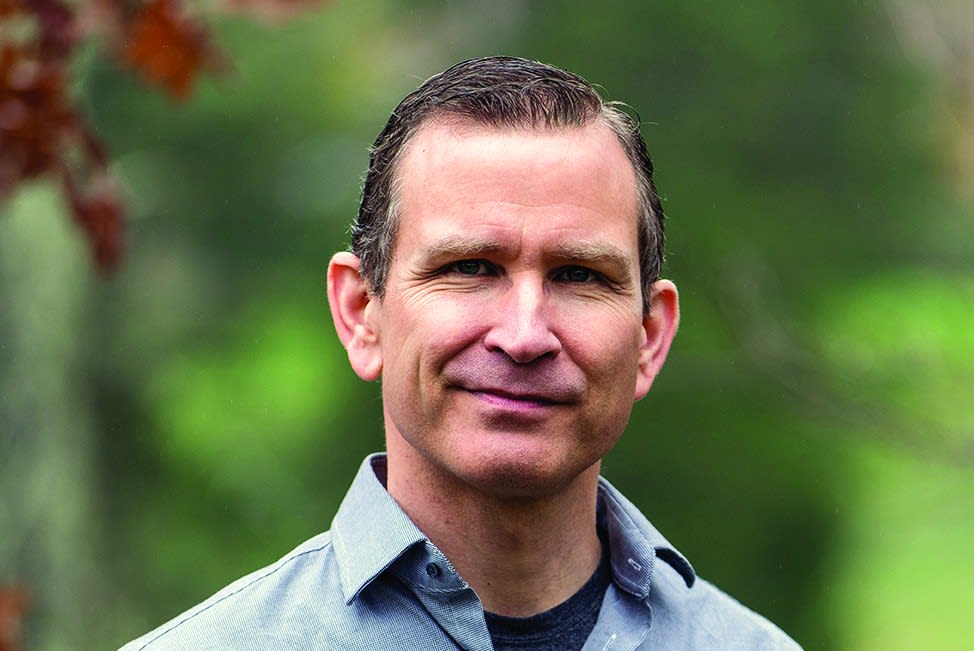

Nonetheless! I have with me today someone who has made a career out of talking about it, in about as energetic and comprehensive a way as you could possibly ask. His name is Bruce Friedrich. He founded and runs the Good Food Institute, a network of think tanks researching plant-based and cultivated meat. Most notably, he has a new book out called Meat: How the Next Agricultural Revolution Will Transform Humanity’s Favorite Food — and Our Future.

The book posits that the environmental harms of meat are real and rising, but that meat consumption is also rising and unlikely to do anything but continue rising in the foreseeable future, and thus the only real solution is affordable meat alternatives. Friedrich argues that those alternatives are akin to renewables in their early days, in that with some sustained investment, they could be put on an S-curve of accelerated development and see rapidly declining costs.

I admit that I am somewhat skeptical, but I am nonetheless delighted to have Friedrich here today to make the case — to tell me how meat alternatives will, if you’ll forgive me, save our bacon.

With no further ado and no further bad puns: Bruce Friedrich, welcome to Volts. Thank you so much for coming.

Bruce Friedrich

Thank you so much for having me. I’m delighted to be chatting with you.

David Roberts

Congrats on the book, Bruce. It is amazing, comprehensive, incredibly educational. I have a lot of questions to ask. I want to mostly focus on meat alternatives. I want to get there. But to get there, we need to walk quickly through the argument that leads us there. Two parts of that argument that I want to walk through. The first part is about the environmental harms of meat — i.e., we can’t just sit back and do nothing. This is bad. We have to do something. The second part is, but people aren’t going to stop eating meat. Thus, we need meat alternatives.

I want to talk about the meat alternatives. But let’s just start with — this is what I want to spend the least amount of time on, but in a sense, it’s the most important part. It’s the reason we’re doing all the rest of it, which is just the environmental impacts of meat. This is, I think, four chapters of your book, so it’s a little crazy to ask you to boil it down, but maybe you could just give us the 3 to 5 minute version of what meat is doing, with a focus on climate. Maybe start with climate.

Bruce Friedrich

Yeah, absolutely. And thank you very much for asking the question. It’s chapter two — the environment. Chapter one is hunger and malnutrition, chapter three is antimicrobial resistance, chapter four is pandemic risk, and chapter two is the environment. I think it’s often helpful to remind people of just how inefficient it is to cycle crops through animals.

According to the World Resources Institute, the most efficient animal at turning crops into meat is the chicken. It takes nine calories into a chicken to get one calorie back out. I’m guessing most people who listen to this podcast are very concerned about food waste, and we should be concerned about food waste. For every hundred calories that are produced globally, 25 to 30 of them or so are lost.

But think about the fact that if you’re going to produce 100 calories of chicken, you’re going to need to produce 900 calories of feed for that chicken. You’ve got a physiological food waste of 800 calories — 800 calories that are produced by our food system but are essentially wasted raising the chicken up to slaughter weight or going into feathers, bones, blood, whatever else. It’s nine times as much land, nine times as much water, nine times the herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizers.

And it’s not just that. Now you’re growing all of those crops and shipping them to a feed mill. You’re operating the feed mill, shipping the feed to the farm, operating the farm, shipping the animals to the slaughterhouse, operating the slaughterhouse. It’s multiple extra stages of gas-guzzling, pollution-spewing vehicles, as well as multiple energy-intensive and polluting factories.

Back in 2006, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization released a more than 400-page report called Livestock’s Long Shadow. They said, whatever environmental issue you’re looking at, from the smallest and most local to the largest and most global — everything from deforestation and biodiversity loss and land degradation, to water use and water pollution, to air pollution and to climate change — animal agriculture is one of the top three causes for things like deforestation and biodiversity loss. It’s far and away number one.

Since UNFAO released that report 20 years ago, we have seen meat consumption go up globally by about 40%, from about 266 million metric tons to 370 million metric tons. The latest numbers on climate specifically are that animal agriculture is responsible for about a fifth of climate change.

We’ve seen analysis — McKinsey economists did some analysis for ClimateWorks Foundation and the Global Methane Hub. The International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis did some analysis that they published in Nature Communications. They said on both land use and climate change, the dividends that we could get from making plant-based meat and cultivated meat — and I would say these are alternative meats rather than alternatives to meat.

Just like your electric car is still a car or your digital camera is still a camera, this is a different way of producing meat. The dividend is about a gigaton for every 10% protein transition, which is the equivalent of eliminating all airplanes at 10% alternative proteins. But eliminating all airplanes doesn’t get you anything in terms of land use dividends. At 50%, 640 to 650 million hectares of land are freed up, which is about the size of the entire Amazon rainforest.

David Roberts

Yeah, could do some reforestation. You could throw some solar panels down there.

Bruce Friedrich

Exactly.

David Roberts

A lot of stuff you could do with that land. Meat is on the most wanted poster for virtually any environmental problem you name, very much including climate change. When I was phrasing the question, I misphrased it. I know that environmental is one set of risks. The first four chapters are about meat’s risks, let’s say. You touched on the environmental ones. Just briefly talk about those other three chapters, those other three big risks.

Bruce Friedrich

The first one is hunger and malnutrition. The Nobel Laureate in economics for his work in this area, Michael Kremer, put together a commission at the University of Chicago that was looking at interventions that could help with climate mitigation, climate adaptation, and food security, which they were defining in the hunger and malnutrition category. They said that because of the land use needs of meat production, what ends up happening — and there’s lots of peer-reviewed research about this, lots of reports from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization — is that smallholders, pastoralists, subsistence fishing communities, end up being thrown off their land.

The world’s poorest people, because of land pressures and pressures to grow crops to feed to chickens and pigs and other farm animals, see the price of cereals driven up. That means more and more people cannot afford a nutritious diet, up to and including hunger and malnutrition. That’s chapter one.

Chapter three is antimicrobial resistance. About 70% of medically relevant antibiotics that the pharmaceutical industry produces every year are fed to farm animals, not because those animals are sick, but because antibiotics both A, cause the animals to grow more quickly, and B, allow the animals to be kept in conditions that would otherwise cause death losses to skyrocket.

This is one of the top two causes of antimicrobial resistance, which the UK government has said is a more certain risk to humanity than climate change. The former head of the World Health Organization said, “We’re literally staring down the barrel of the end of modern medicine, where a lot of surgeries that we take for granted will just be not even possible if antibiotics completely stop working.” Both of the top two causes in this, including this one, are getting worse.

Chapter four is pandemic risk. In July of 2020, the International Livestock Research Institute and the UN Environment Program released a report — 18 of the world’s top zoonotic disease specialists, about 35 consultants on this report — called Preventing the Next Pandemic. They listed the seven most likely causes of the next pandemic. The first one was increased meat consumption. More animals means more potential vectors for disease. The second one was the industrial raising of animals for food, both because the animals are so genetically similar, and also because when you cram 50,000 chickens in a shed, that is a disease factory. The possibility of the next pandemic goes up.

In the book, I go through that, and then I also say, “Look, we’re going in the wrong direction on all seven of the most likely causes of the next pandemic.” We just lived through COVID-19 and are still to some degree on the tail end of it.

David Roberts

Look how well we did, Bruce. I don’t know what you’re so worried about. We aced it.

Bruce Friedrich

Nothing to worry about. But seriously, it could have been a lot more deadly. It could have been a lot more transmissible. It did send 100 million more people into dire poverty — COVID-19 — and it really wasn’t as bad as it could have been. The next one could be significantly worse.

The bird flu in 1918 actually killed more people than World War I by a lot, about the same number of people as World War II. If you look at US death losses, it killed more than World War I and World War II put together. We have a lot more animals. We have a lot more capacity, both humans and animals, to move around. The next pandemic could be pretty disastrous.

David Roberts

That’s a lot to take in quickly. Meat is perversely spreading hunger and malnutrition, screwing up the environment in a dozen different ways, including climate change, making antibiotics work less well, and possibly setting the stage for the next pandemic. All those risks are bad. They’re all getting worse. I think we can take it as established by the first four chapters of your book. Whatever we do, we can’t keep doing this — things are bad and getting worse. We’re nearing thresholds. Something’s got to be done. Let me just pause here. I’m not going to spend a lot of time on this, but I do want to just pause here as an interlude.

Let’s call this a vegan interlude. I personally am not a vegan, not a vegetarian. I feel guilty about it, but I’m not. But I do want to have their perspective, at least. Let’s just speak for them briefly. Let me just say, putting on the hat of a militant vegan, you have just made the case that meat is terrible. Terrible for the environment, terrible for society, terrible for land, terrible for our health, possibly our respiratory health, our heart health, whatever. That’s one fact.

The second fact is we know that human beings can thrive without meat. Millions of people do it. In the vast, vast majority of cases, there might be some edge cases, but in the vast, vast majority of cases, we know that it’s possible to live a perfectly good, healthy life without meat. Those are the only two facts we need. It’s a monstrosity. It’s awful. It’s destroying land and people and society. It’s a bad thing. We could stop without harm, really, which is unusual.

There are a lot of instances where we’re using fossil fuels, where we don’t have alternatives, where we can’t just stop without quite a bit of harm. This is a place where we could stop harmlessly. What we’re doing is a monstrous, historic, moral crime with our eyes wide open. All the discourse about it is mostly an effort to avoid just looking that basic fact in the face.

Now, I think you and I would probably agree that that is not a particularly useful perspective. You and I probably agree that if you’re trying to change public opinion, that’s probably not the best approach. You probably don’t want to go out starting by accusing people of being horrendous moral criminals. But just between us, in our heart of hearts, it’s true, isn’t it?

Bruce Friedrich

I don’t know that there’s a difference between a heart-of-heart way of looking at something and a utilitarian way of looking at something. The vast majority of people are good people who are trying to make the world better. Everybody is the hero of their own story, obviously. I think there is something physiological about the way that human beings are programmed such that it’s just true that as economies develop and the population grows, meat consumption goes up. Literally every year since FAO started measuring, and I’m sure every year before that as well, meat consumption has gone up and up and up.

All of the predictions are that that is going to continue as long as the global economy gets larger and as long as global population grows. We’re going to see both per capita meat consumption go up with the economy getting larger, and obviously more people mean more per capita meat. The lowest predictions for 2050 are another 50% more meat than we have now. If that happens, according to the World Resources Institute in a report that they put together with the World Bank and the UNEP and the UNDP, we’re not going to have any forests left, we’re not going to have any savannas left, and we are going to absolutely blow through even backup climate targets.

The only two things that anybody is thinking about that might change that are: one, let’s lean in on convincing the world to eat less meat, which we’ve been doing for at least 55 years. Diet for a Small Planet came out in 1971, and it makes the environmental and the global hunger argument extremely well. So 55 years ago, 1971, and meat consumption just goes up and up and up. At this point, if somebody is not changing their diets, it’s not due to lack of information. It’s due to the fact that it’s really hard to change diets. Vegetarians and vegans get incensed when you say that.

David Roberts

They really do. Although I’ve never been able to do it myself. I’ve tried at points in my life to go without meat. I feel it physiologically. I feel unsatisfied perpetually, and that lasted for weeks or months when I tried. But then on the other hand, I have the vegetarian on my other shoulder saying, “Give me a break.”

Bruce Friedrich

Some people change. A lot of people change. Most of the people who have started plant-based meat and cultivated meat companies have changed. I’ve personally changed. I’ve been a vegan for 38 years. But what I’ve learned in 38 years of veganism is that most people aren’t going to do it. In the book I make the point, I say, “Look, I think this is systems one thinking.” Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Laureate in economics, his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow.”

There is something ingrained in the vast majority of people that the fat in meat, the umami in meat — for most of humanity, we have not known where our next meal is going to come from. Consequently, we crave highly calorically dense foods. It’s no longer to our benefit, but we deny it at our peril if what we’re trying to do is make a difference on the meat problem.

This is very much like what the energy community has recognized to be true about energy consumption. The world has consumed more energy every single year since forever. Other than a blip for COVID, other than those kinds of shocks, we’re just not going to convince — it is not a reasonable strategy to try to convince the entire world to consume less energy and walk more.

We need renewable energy as one tool in the toolkit. That doesn’t mean that you get rid of other tools, but it does mean that renewable energy is essential. It does mean that electrification of transport is essential.

What appears to be true, unless somebody’s got some new strategy that they’re holding in abeyance to spring on us at some point: despite overwhelming success in focusing attention on the environmental and global health and other animal protection consequences of meat consumption, people eat more and more meat.

Let’s add a tool to our toolbox. Let’s learn from what renewable energy and electrification of transport have done. Let’s give consumers what they love about meat. It’s delicious, it’s affordable, principally. Let’s use science to biomimic the precise meat experience using plants. Let’s use science to grow actual animal meat, but doing it in cultivators that look like fermenters for beer instead of on live animals, and we can slash the adverse consequences, eliminate the contribution to antimicrobial resistance and pandemic risk, and slash the contribution to hunger, malnutrition, and the range of environmental harms.

David Roberts

It would be fair to say you have no problem with other people out there trying to convince other people to stop eating meat. You have no problem with stopping eating meat. You have stopped eating meat. You just think from a purely pragmatic point of view, the quest to persuade any substantial portion of humanity to go along with that is probably futile. Thus, this is the only remainder — the only other way to go.

Bruce Friedrich

I think it’s the only other way to go. It’s also the case that if you look at land-based and food-based climate solutions, this appears to be the only one that can spread in the same way that renewable energy and electric vehicles can spread, which is to say it’s market-based and it’s science-based.

You look at the history of solar and you have Germany, the US, Japan, and China responsible for the massive downward trajectory in prices and consequently the massive upward trajectory — the S-curve, we’re on it now — trajectory for decarbonization of electricity. That’s basically what happened with electric vehicles.

We can do that with plant-based and cultivated meat. It doesn’t appear likely that we can do that with anything else. McKinsey, economists for ClimateWorks Foundation and the Global Methane Hub, looked at all of the methane, agricultural methane interventions. They looked at interventions for food loss and waste —

David Roberts

Landfill capture, etc.

Bruce Friedrich

Exactly. The principal ones they looked at: rice mitigation, food loss and waste, methane inhibitors and other cattle-based methane reduction interventions, and alternative proteins. They found that of the economic benefits of these technologies, 98% went to alternative proteins. Because this is something like renewable energy. Once you get to the point at which markets can take over without subsidies, then it just becomes perpetual. The Wright’s Law — decrease in prices based on increase in adoption — just keeps going. It’ll stop at some point.

David Roberts

Will it? I’m going to return to that analogy. I’m going to return to that analogy soon. We’ve established meat’s a big problem — big environmental problem, health problem, etc., number one. Number two, it’s unlikely people are going to stop eating meat. Meat consumption has gone up every year since we started recording it. It’s probably going to keep going up. Ergo, the only way out of this dilemma is through alternative meats. Let’s talk about alternative meats.

It seems to me — I’m not far from an expert on any of this — but it seems to me like plant-based meats and cultivated meats are very, very different things, very different industries, but you sort of lump them together. You talk about alternative meats throughout the book as kind of a unit. I’d like to hear you talk about that a little bit. Why do you think it makes sense to lump those together?

Bruce Friedrich

Your intuition aligns to the intuition of a lot of people. If we were talking about wind energy and solar energy, you might say, “They’re radically different ways to produce energy.” The thing that unites them is that they allow you to decarbonize energy production. With plant-based meat and cultivated meat, it’s definitely the case that we start at negative 100 on plant-based meat.

We have to first explain to people that our goal is not to convince you to pay more for products that you like less, which has been the — this has been what plant-based meat has been for a really long time. Veggie burgers have been veggie first and burger not at all.

David Roberts

Form factor wise, exactly, that’s about it.

Bruce Friedrich

But nobody was trying to make them taste the same. Nobody was trying to make them cost competitive. If you’ve got a $600 million industry marketing to flexitarians and reducetarians and people who wanted to eat less meat, that’s still a significant industry in the United States. Ten years ago there was no Impossible Burger. Ten years ago there was no Beyond Burger. They both launched — the Beyond Burger launched in May of 2016, the Impossible Burger a few months after that. Up until that point there really was not the idea that we might biomimic the precise meat experience using plants.

Then Ethan Brown and Pat Brown came along — no relation — founded Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods. The basic brainstorm was, science can do this. We can make plant fats and proteins behave like animal fats and proteins. We can mimic the umami flavor. For the same reason that these are a massive environmental boon — they require far fewer resources at scale — they will also cost less.

One of the reasons that we insist on saying alternative meats rather than meat alternatives is to underline the fact that we are not going for something that people have to sacrifice at all to consume. We’re going for something that nails the experience. No innovation comes out fully formed. If you look at something like the automobile, from 1900 to 1910, 500 automobile companies failed, including Henry Ford’s first automobile company. In 1908, he introduced the Model T. It was the first car that average people could operate. Up until 1908, automobiles were really hard to operate. You had to be very strong to turn the crankshaft. You had to be a mechanic because they were breaking down all the time and they were really expensive. Woodrow Wilson, president of Princeton at the time, said, “Automobiles will never be more than a plaything for the idle rich.”

Flash forward 100 years and you’ve got interstate commerce. The NASDAQ loses during the dotcom bubble 80% of its value. Pets.com goes out of business. Amazon drops 97% — its stock value from $213 to less than $6. The commentary was ruthless: “Who would ever want to buy pet supplies online? Who are you kidding? When is this Jeff Bezos character ever going to turn a profit? This is all snake oil.”

But we got landlines, you no longer had to dial up, people got used to ordering things online. We gave people what they like about buying things — confidence that the things were going to be high quality, etc. You don’t have to go to a mall. Now Chewy is worth $13 billion, market cap 30 times what pets.com was ever valued at.

The plant-based meat products are not good enough yet and they cost too much. If you look at the obituaries for plant-based meat in the media, those are the two things that are cited for why they have failed. Nobody ever said these are going to be fantastically successful while they cost too much and don’t taste good enough because consumers want the meat experience. What is it about the science that makes anybody think that they can’t biomimic the meat experience? Maybe they can’t. Nobody’s done it yet. But we haven’t tried very hard and we don’t have a Plan B.

David Roberts

I was talking to a guy who does virtual power plants. It’s just a bunch of distributed energy devices coordinated to act as a single entity. Part of what he’s trying to do is reach a point where that looks to a grid operator exactly like a power plant, that it can pass something akin to a Turing Test. You know what the Turing Test is? “Can a virtual power plant fool the grid into thinking it’s a real power plant? Can it effectively act identically to a power plant?”

I’ve been waiting for you to introduce something similar in this part of your book. It seems like this is what you’re describing. The goal here is a plant-based or cultivated burger that in a blind taste test could not be distinguished from meat. Is that the Holy Grail here? That’s what you’re after. There’s no name for that test. You should be claiming this IP, Bruce. This should be the Friedrich Test.

Bruce Friedrich

That’s funny. I like it. The thing that we say in the book — what everybody at GFI, our fundamental focus is — get the products to a place where they taste the same or better and cost the same or less, and they have to be nutritionally superior as well. As I talk about in the book, that’s baked in for both plant-based meat and cultivated meat. That’s not something that we need to solve, but we do need to solve taste parity on the plant-based side and we need to solve cost parity on both sides. That’s really our focus.

We think you do that by building a maximally robust scientific and engineering ecosystem. The way we think you do that is government support. The clarion call of the book is that governments should be supporting the science of plant-based and cultivated meat and they should be supporting infrastructure and manufacturing buildout. The reasons that they would do that are the same reasons that they would do that for renewable energy or electric vehicles. Probably not environmentalism.

David Roberts

We’ll return to this question too. I want to start by looking at the extant markets as they exist today. I read that investment in alternative proteins dropped by almost 50% in 2025. I remember, as a member of the public, veggie burgers kind of having their moment and then they faded. Then Impossible came along and popped up in Burger King and kind of a thing. Then that faded.

My impression now is that the hype cycle is in a trough, that investment is low and that public faith that this is ever going to get where it needs to go is low. That’s on the plant-based side, which has actually had some time. The cultivated side, as far as I can tell, is not an industry yet. They’re not actually selling any products yet. Is that a fair description on both sides?

Bruce Friedrich

It’s pretty close to fair. We’re definitely in the trough of disillusionment. On the plant-based side, the products are not yet competing on price or taste. Some of them, a very small number, are pretty close on taste, but none of them are anywhere near where they need to be on price.

On the cultivated meat side, there are a very limited number of restaurants on the planet where you can get cultivated meat. There is not a meaningful market by any stretch of the imagination. The rebuttal to that is that year after year after year, the amount of government support goes up every single year. The number of papers published goes up every single year. The number of scientists focused on this goes up every single year. The number of conferences goes up every single year.

It’s struggling on the private sector side, but because of the economic gains that are to be made here, as well as food self-sufficiency and food security arguments, governments are funding science in this space. It’s early days, as you and Mike Grunwald were talking about. We have a lot of science and engineering and scale-up left to do, but it is moving in the right direction despite some headwinds on the private sector side.

David Roberts

Let me ask about this. The premise here is that with sufficient science and investment, this will get on a cost curve. Volts listeners are very familiar with cost curves. You double deployment and costs go down by some percentage. That’s held reliably true for a number of technologies, a number of clean energy technologies.

But it is not the case that all technologies get on learning curves. We’ve done a lot of episodes on this — which ones do and don’t. It’s not obvious to me that something that is at root biological is going to mimic technology in terms of getting on that curve. At the very least, that seems like a rather large assumption, that perfecting a biological process is going to get on that same curve that tech processes do. Why should we assume that that’s true?

Bruce Friedrich

I dive into that in chapter nine. I talk about Wright’s Law and learning curves. I talk about how that has worked for EV batteries and actually cars and airplanes and solar and wind and refrigerators — name it — which are things that have to be produced. I make the case: both A, we are seeing that on the cultivated meat side — the first cultivated burger cost €250,000. It’s down a decade later by a factor of 100,000. It’s down by 99.999%.

David Roberts

I can’t do that math in my head, Bruce, what’s the —

Bruce Friedrich

$3 a burger.

David Roberts

$3 a burger.

Bruce Friedrich

— to produce. It’s still twice as expensive as producing beef and that’s at a pretty small scale. What’s it going to look like to produce it at mass scale? There are going to be some engineering challenges to that.

But media costs — there was techno-economic analysis done where the author said media costs cannot get below $6.50. They’re now below 50 cents. In his argument this was not going to be possible. It really does remind me of just a decade ago, the number of people who continued to be in denial about whether solar costs could continue to come down, EV battery costs could continue to come down.

We are innovating on both the plant-based meat side and the cultivated meat side. Here is a case where your previous observation — the science of both of these is radically different. It may be that the cost curves on one of these can come down and down and down and the cost curves will work for one and not work for the other. For the book I chatted with 30 plant-based meat scientists, 30 cultivated meat scientists. They all are very enthusiastic about the idea that the cost curves concept and S-curve growth, once we hit price and taste parity, is going to work.

They point toward — and I talk about this in the book — what is an intuitive observation. If something requires a fraction of the resources of something else and if something requires far fewer stages of production — even for chicken, you have a ninth the inputs for plant-based chicken, a third the inputs for cultivated chicken, both of those are even pilot plant numbers. They’re likely to get even better for the alternative meats.

Instead of having to grow the crop, ship the crops, you don’t have the feed mill, you don’t have the farm, you basically sub the slaughterhouse for the plant-based meat or the cultivated meat factory. You have far fewer stages of production, far fewer resources required. It’s going to take time to ramp up the oil production, it’s going to take time to ramp up the protein production.

For cultivated meat, it’s going to take time to ramp up both the production infrastructure as well as the media to feed the small samplings of animal fat or animal muscle. But it’s hard to imagine that at production scales these will not be less expensive and significantly less expensive.

Then you’ve just got, can science biomimic the precise meat experience using plants? Can science produce meat at 200,000 liters and cause the animal fat and muscle to grow at that size? It’s never been done before. But I haven’t talked to anybody who thinks, “No, there’s some scientific reality that makes the physics of this impossible.”

David Roberts

There is a manufacturing insight that says with sufficient scale, costs of production converge over time on the costs of materials.

Bruce Friedrich

Yeah, exactly.

David Roberts

And so many fewer and much cheaper materials going into this process.

Bruce Friedrich

Not yet, but the science indicates that that should be possible. In all of human history, we put about $3 billion into cultivated meat. A journalist wrote, “Three billion dollars have been poured into this. Where’s my cultivated burger?” That’s less than the cost of one EV battery factory. If you’ve already got a massive biopharma company, that’s about the cost to bring two drugs to market. It’s been spread across 150 companies in 10 years. It’s just not that much effort.

That’s one of the reasons that in chapters one through four, I’m saying, the stakes on this, no pun intended, unless you have some alternative plan for solving antimicrobial resistance, for solving hunger and malnutrition, and for solving the range of environmental harms that come with conventional meat production, this is the sort of thing that we should muster the resources to try to make it work. The science looks pretty good.

David Roberts

I want to ask you a science question because one of the things I found really interesting is, the vibe I get from later chapters is that you kind of think that it might not be possible to get there with plant-based. It seems like in the long term you have more hope for cultivated meat. Remember, when we talk about “get there,” we’re talking about getting to a place where if I sit down with a plant-based burger, I basically can’t tell the difference. You, it seems, are somewhat skeptical that plant-based is ever going to get there. Is that accurate?

Bruce Friedrich

It’s accurate, but I should add the caveat that I am not convinced that the science is harder. I am convinced that the science is less intuitive. In the book I look at things — there are a lot of inventions, as Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson talk about in Abundance, that are waiting to be invented. You can fail at something because the science doesn’t work. You can fail at it because you didn’t bring the will.

A lot of people’s intuition on plant-based meat is that it’s not possible. That intuition is backed by what looks like a lot of effort that hasn’t been successful. In the book, what I say is, most of this effort hasn’t even tried. All of these companies that came along and said, “We’re the next Impossible Foods,” and they said, “We’re going to have a product in six months. We don’t have a science team.” Impossible Foods — Pat Brown is one of the greatest scientists currently living. An incredibly impressive human being. Took him tens of millions of dollars and five years to create the Impossible Burger.

These first-time entrepreneurs, fresh out of business school, come along and they’re going to squish some ingredients together and call it an Impossible Burger. They raise a lot of money to do precisely that. They fail and people go, “The plant-based meat endeavor failed.” What happened was they didn’t try; they were intentionally the next Gardenburger saying they’re the next Impossible.

David Roberts

This gets to a larger macro problem with scientific innovation generally, especially in capitalist cultures, which is that the amount of sustained attention and investment you need over time to get plant-based to where it needs to go doesn’t seem like something a single company can do while also making money in the interim. It seems like the kind of thing where you need government, you need some public subsidy if you want that sustained research program.

Bruce Friedrich

I think you probably need that on the cultivated meat side too. But at least the cultivated meat entrepreneurs and innovators are focused on the right target.

David Roberts

You don’t think the plant-based meat industry has sufficiently taken your goal upon itself. You don’t think that they are shooting for the right target?

Bruce Friedrich

No, and I make that point pretty explicitly in the book and give a whole bunch of examples. One of the things that’s really interesting is if you go to a conference on cultivated meat — the first one was just a little over 10 years ago, and now there are dozens every single year — you go to these conferences and there are a lot of innovators who are focused on B2B. There are basically four things you need to solve on cultivated meat and there are startups doing all four of those things.

The point that you just made is a really good one. It’s really hard to have an R&D company. It’s also really hard to have a company that makes products for people to buy. You multiply those two incredible difficulties, and that’s what all of the plant-based meat companies are right now. Not quite all, but just about all of them. On the cultivated meat side, it is probably harder science, but everybody understands the assignment and that is what they’re focused on. It’s really hard to get mixed up on the cultivated meat side, whereas most of what’s happening on the plant-based side is noise.

The other thing that I hadn’t thought of until Aaron Rees Clayton, one of our scientists, pointed out to me, is that every single human being on the planet who is currently working in tissue engineering has the basic skill set that’s necessary to understand what needs to happen for cultivated meat to be successful. Nobody has ever been challenged to figure out how to mimic the umami flavor of meat. Nobody’s ever been challenged to figure out how to get plant fats or proteins to behave like animal fats or proteins.

David Roberts

But I thought that’s what Beyond was trying to do.

Bruce Friedrich

Yes, those two companies, and there are a handful more now. My point is that the people doing that do not come in with the scientific expertise necessary to figure out how you solve plant-based meat. Nobody has ever — every tissue engineer, literally, I don’t know how many tissue engineers there are, but many thousands of them working in human therapeutics — they all have the requisite skill set for cultivated meat. The only application for trying to convince plant fats, proteins, and flavors to behave like animal fats, proteins, and flavors is that, so the only people doing it are doing that.

It’s probably dozens of people, maybe we’re past 100 now, but thousands and thousands and thousands of people, and they all come in with the right skill set. The two people who were the fathers of cultivated meat are both medical doctors. One of them is also a PhD in tissue engineering — Mark Post, the person who made that €250,000 burger with money from Sergey Brin back in 2013.

The other one is Uma Valeti, the founder and CEO of Upside Foods, then Memphis Meats. He was the president of the Twin Cities, both the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association. He trained at Mayo in tissue engineering as a medical doctor. Tufts is one of the centers, maybe the center in the United States — Tufts and NC State and UC Davis. At Tufts, it’s David Kaplan, who was the chair of the biomedical engineering department at Tufts, who’s leading the efforts on cultivated meat at that university. They come in with the right skill set. You need a lot of different people with a lot of different skill sets.

The overall scientific challenge may be easier, but we don’t have massive numbers of scientists who have the right skill set. Everybody has to be retrained on the plant-based meat side. I talk to a lot of people; everybody thinks the science can work, but it could be that the practical challenges end up being insurmountable. My hope is that we’ll be able to create the enthusiasm and the focus and the support to make both technologies work. But if I were to predict, one will work and one will not; it would be cultivated that works.

David Roberts

This gets a little bit back to your renewables analogy. One thing I wanted to ask about: one way that the countries you cited earlier stimulated research and activity in renewable energy was it wasn’t all carrots. There were sticks involved. It wasn’t just governments subsidizing research. It was also restrictions on fossil-based energy that created some of that will. Most of what you discuss in the book is carrots. I wonder if you don’t think that maybe one of the things that would create more activity on the plant-based side is just some sticks, something to force that urgency, some kind of penalties on meat. You think that’s just impossible? Why?

Bruce Friedrich

The main thing I think is that we can convince governments that it is in their interest. The number one person who I wanted to write the foreword to the book is Caitlin Welsh. She was at the State Department and then the National Security Council. She was Obama’s second term, almost all of Trump’s first term at the National Security Council. She’s now director of global food and water security for the Center for Strategic and International Studies. She spearheaded a report that CSIS did about alternative proteins, talking about the food security, food self-sufficiency, and economic competitiveness arguments for alternative proteins. They end up saying that the US government should lean in on alternative proteins in the same way that it has leaned in on things like advanced chips for AI and biopharma.

David Roberts

You think this is part of that because there’s a general, I would say, global pullback from the kind of rah-rah global trade attitude of the 90s and 2000s. There’s been a pullback away from globalization. You think this is part of that story?

Bruce Friedrich

I think it’s a response to that story.

David Roberts

The fact that we rely on trade to feed ourselves is increasingly being viewed as a liability, as a weakness.

Bruce Friedrich

It’s always been viewed as a liability and a weakness that’s coming into even more stark relief now. Countries have always wanted to be food self-sufficient, but certainly the global dynamic that you’re describing right now accurately puts into stark relief just how risky it can be to not be food self-sufficient. That’s one of the reasons that we’re seeing the earliest leaders on alternative proteins were Israel and Singapore because they’re tiny and they don’t produce that much food.

David Roberts

But we do — we have giant ranchers and a lot of land. Why wouldn’t food security for us, especially if you’re talking about the US federal government, which is, shall we say, heavily influenced by Big Ag, why wouldn’t the response to food security be, “Let’s just grow more and raise more meat in the United States”? Why does that necessarily militate for alternatives?

Bruce Friedrich

It doesn’t necessarily militate for alternatives, but the two things that CSIS says that’s responsive to that: one is that no matter what we think about the fact that we live in a global economic and agricultural marketplace, we do. When we retrenched or pulled back on things like renewable energy and electric vehicles, what we basically did is said, “Hey China, you can dominate these industries.” Do we want to do that with agriculture and meat production? That’s thing one.

Thing two is, even in the United States, all of those extra stages of production add fragility and vulnerability to the way that we produce food. It really is an incredibly precarious food system that is quite fragile. If we can tighten it up, that will also increase the US’s food security. The other thing they say is this is a multitrillion-dollar opportunity and the US should play for it. Especially in seafood. We’re something like 2% of global seafood, which is a $500 billion market. Right now, we have the two global leaders on plant-based meat, we have three of the five or six global leaders on cultivated meat. But we could lose that pretty quick.

David Roberts

It’s nascent, but we are currently in the lead, you would say, the United States.

Bruce Friedrich

We’re in the lead for startups and innovation and we certainly have the capacity to be in the lead for overall science. But no, China has taken over the lead. If you look at patents and cultivated meat, the 20 most active patent holders, patent applicants — eight of them are Chinese, three of them are from the US, three from Korea, three from Israel. We are winning on innovation and startups, where Israel is second, but we’re way out in front. We’re winning on number of scientists and scientific innovation. Maybe we’re tied with China, but they came into it late and they’ve already lapped us.

David Roberts

That’s just what we did with renewables. We had the IP, we had the research, we had the science, we had the innovations, and then we just handed it to China to do the manufacturing and the scale. It would be hilarious, darkly hilarious, if we just did the exact same thing all over again on this industry. Which leads me to the question: how does Big Ag feel about this?

One of the reasons I’m a little skeptical about the analogy with renewable energy is that at the very least there’s some public excitement about renewable energy. There’s a lot of money being made. But in the US, insofar as this comes up, it seems people are against it. There’s a lot of people against it. They’re suing to prevent these people from using the word meat. Oklahoma or one of those states out there is doing some ridiculous thing where you can only call it meat if it’s raised in a field or something. It seems there’s backlash, not support from the meat industry. What is the disposition of Big Ag toward this?

Bruce Friedrich

This is one of the interesting places where Big Ag needs to be disaggregated because the largest meat companies are enthusiastic. Tyson Foods, JBS, Cargill, and then their representative at Washington, the Meat Institute. They’re not taking a “yes, let’s go all in on this” stance, but they are investing and they are basically supportive.

David Roberts

Interesting — in cultivated or plant-based or both?

Bruce Friedrich

In both. This is one where I think there’s an advantage to alternative meats relative to energy. The meat industry, they don’t own the farms, they mostly don’t own the slaughterhouses. If they can lose some of the fragility and go with larger profit margins, that’s pretty appealing. I have heard people in the meat industry say, “We don’t want to be Kodak, we want to be Canon.”

But what you just described is also real. There are mostly ranching interests that are pushing back. As you will have seen in the book, in chapter 10, what I try to say is right now it’s really hard to be a farmer, it’s really hard to be a rancher. Alternative meats are responsible for none of that because we basically don’t exist as an industry. What would it look like to shift away from the “get big or get out” thing that has made it so hard to be a rancher or a farmer?

We have done some economic modeling that looks at things like as you shift to alternative proteins, it frees up so much land that, for example, Green Alliance, a climate and environment think tank in the UK, looked at 10 European countries and said, “This is how much land’s freed up. If you take a third of that and devote it to human food, you can get to food self-sufficiency for eight of the countries and net food self-sufficiency for the 10 countries put together.

You take a third of it and you rewild and move to tree planting. You can sequester so much carbon on that rewilded land that you get about 250 million metric tons of sequestration. Then you take a third of that land and you shift to regenerative/agroecological practices — legitimately regenerative and agroecological practices, not the greenwash version. You can 4x the amount of land for regenerative ranching and regenerative farming.

It feels like working with farmers and ranchers on all three of those: let’s shift to higher value products for human consumption. Let’s pay farmers and ranchers to rewild and rehabilitate land. For the meat that farmers and ranchers are going to be raising, let’s make those animal products — the meat, dairy, and eggs — in a more regenerative and agroecologically sustainable way.” That’s one of the things I’m trying to do in the book.

David Roberts

That makes total sense to me, a fruity coastal liberal. But how do the ranchers — this is something we learned about the coal industry, right? You can go to a coal worker and say, “We’ll just pay you to retire and you’re fine, you’ll have all the money you need. We’ll pay for your health care.” A lot of them will just say, “No, screw you.” There’s more to this than the money.

There’s more to this than — there’s an irrational, or maybe it’s a rational, cultural attachment to these things that goes beyond mere money and inputs and outputs and profits. I wonder how deep the attachment, not just the attachment specifically to raising animals on land, goes, how deep that attachment goes and how rational it is and how rational they are in responding to these incentives.

Bruce Friedrich

It’s certainly the case there are not many chicken or pig farmers who are raising animals in anything other than industrial systems. We really are just talking about dairy farmers and ranchers. Obviously there are as many different views of everything as there are dairy farmers and ranchers. We have seen real interest in having these conversations. I think there is a distrust — a distrust of Washington, a distrust of policies and regulations — that comes inherently with the ethos of being a rancher. But I don’t think that most people who are ranchers or dairy farmers would feel — who knows better the ecology of the prairies of the West than the ranchers?

If we can legitimately get to a place where we are paying them to rewild part of their land and they’re able to raise animals in a more agroecologically sustainable way — you see these documentaries and a lot of these ranchers, especially the documentaries like Kiss the Ground and those sorts of documentaries, the ranchers are legitimately enthusiastic about care for the animals and care for the land. In a lot of these documentaries, they really hate the day when they have to take the animals to slaughter, which is fascinating. Combine those observations with the fact that 98% of beef cattle in the United States spend the last half of their lives on feedlots — that is a horrible existence, in addition to being environmentally catastrophic.

If we could shift to a world where all of the beef that was produced came from animals that didn’t see a feedlot and actually had the opportunity to graze and restore lands in a truly holistic management system, that feels like the kind of thing that ranchers could get behind, but it would require more land. Where are you going to find that land? Our hypothesis is that alternative proteins is how you free up the land to allow that to happen.

The World Resources Institute, the report that they did with the World Bank, UNEP, UNDP, said, on our current trajectory, we’re going to need 3 billion hectares of additional land or serious gains in crop productivity. Those have largely leveled off. That literally means no more forests, no more prairies, no more savannas. That doesn’t make the kind of ranching that could be sustainable possible.

David Roberts

You said there are four areas where cultivated meat needs work. We’ve been dancing around, but I would like to hear a little bit about the science of cultivated meat. Maybe people don’t even know what this means, but the idea is you are using biofermentation to grow tissue in a vat. That’s what we’re talking about here. Let’s run through those four areas just to give us a sense of what these scientists are doing, what they are trying to figure out?

Bruce Friedrich

A really good way to intuitively think about it is just like you can take a seed or a cutting from a plant, bathe the seed or the cutting in nutrients, and grow a whole plant, you can take a small amount of fat or muscle from an animal — a sesame seed-sized amount of fat or muscle — and grow basically unlimited additional fat and muscle. You’re doing it, as you said, you can call it in tanks, but it basically looks like a brewery. You have the fermenters for beer, we call them cultivators for meat. You end up with your friendly neighborhood meat brewery, essentially.

David Roberts

Just to be clear, what comes out on the back end of this process is flesh. I don’t even know if we have a vocabulary for it, but on a molecular level, it is meat.

Bruce Friedrich

Just like you can use a seed or a cutting to grow a plant and it’s still a plant. For human medicine, you can grow an ear and it’s still an ear. The thing that makes this so much easier is it doesn’t have to be attached to a body and continue to live another number of decades or whatever.

David Roberts

Right.

Bruce Friedrich

Just like you might have a variety of seeds, you’re going to have a variety of different samples of animal muscle or animal flesh. Figuring out how to develop those so that they can grow effectively is one of the critical technology elements. Just like if you’re going to have a greenhouse, you’re going to have the structures that the plants grow on. In the case of meat, it’s a scaffold. That’s how you can grow whole-cut animal meat.

If you’ve got a greenhouse, you’re going to have fertilizer and light and the other things that go into causing the plants to grow. Here you have what’s called media, and that’s the aminos and the carbohydrates and the other elements that cause the animal meat to grow. Finally, you have the cultivators, the massive tanks.

We have a lot of innovation to do across all of those, although the one that we have made the least progress on is that last one. There’s an Australian company called Vow, their chief technology officer came to them from SpaceX and they have done some remarkable things. It was assumed that the cheapest way to grow meat in cultivators was going to be to repurpose bioreactors from biopharma.

What Vow discovered is that they can get to a fourth at this point. It’s very early on, lots of innovation still to come. They can strip the bells and the whistles, the things that you don’t need. If what you’re doing is growing meat for food as opposed to what you’d be doing it for, for therapeutics, they can get to a fourth the cost of even a reconstituted secondhand bioreactor from industry, which is interesting. We still have a long way to go to be producing at 200,000 liters. Just a lot of innovation to do.

David Roberts

I’m guessing when you talk about innovation, you talk about figuring out how to make things grow faster, figuring out how to target textures and tastes. Are we to that granularity yet where you can set out to design a particular texture?

Bruce Friedrich

Oh yeah, absolutely. Lots of companies — chicken, pork, beef, salmon — are producing a lot of meat. One thing is this is bipartisan. There were 10 Republican members of Congress who, on the back of a report out of China about cultivated meat, wrote to the Department of Homeland Security and the Director of National Intelligence saying, “China is doing this. What are we doing to make sure that we are competing?”

All over the world, the idea of leaning in on economic competitiveness, the idea of wanting to be food self-sufficient, is bipartisan. Government support is going up every single year. Number of scientists are going up every single year. Ten years ago there were four scientific papers on cultivated meat that had ever been written. Now we’re producing more than 160 per year. There were seven cultivated meat patents in all of time. Now there are more than a thousand. A lot of things are going in the right direction.

David Roberts

I think this is a question that comes up for a lot of people: project out maybe five years of some intensive scientific work, research, innovation, and the cultivated meat people can replicate the taste and texture of ground beef or chicken.

Bruce Friedrich

They’re doing that now. A lot of companies are doing that now.

David Roberts

They’re getting where they can mimic extant meats. What I wonder is, with a big enough, wealthy enough industry, are we going to start seeing bespoke meats, novel meats, like meats with new tastes and new textures that we have not yet encountered in the wild? Do you think that is going to be a thing?

Bruce Friedrich

Two things. There are probably 100 companies now. It’s pretty easy at this point because costs have come down so far. Ten years ago, if you wanted half a chicken nugget, it was going to be thousands of dollars. That’s literally the first thing that I consumed, as I talk about in the book, and now that’s probably tens of dollars.

I talk in the book about 200 people at the TED Countdown conference being fed cultivated chicken. Nine years after it was thousands of dollars for half a chicken nugget, 200 people were dining on cultivated meat. It’s relatively inexpensive to do now because costs have come down so astronomically. There are certainly dozens of companies who are right now producing things that are indistinguishable from ground chicken, beef, and pork.

David Roberts

When you say indistinguishable, do you really mean indistinguishable? Have there been blind taste tests? Do you mean not close, not an approximation, but genuinely indistinguishable?

Bruce Friedrich

Mike said on your podcast what has been the experience of a lot of people, which is that it’s better because so much factory-farmed chicken flesh now is tougher, not really very good. But yes, it is being served regularly to people and they say it competes with the best animal meat that they have consumed.

David Roberts

I didn’t know we were that far along.

Bruce Friedrich

It’s still way too expensive. The polling is very clear. People aren’t going to pay more for it, but the science is there. It’s still twice as expensive as beef, which means it’s five times as expensive as chicken to produce. It’s going to take some time to get there. Figuring out how we scale it up is going to be tough. The scientific progress, on the basis of literally 10 years ago there were four science papers ever published, there was one company that had raised a dime — Upside Foods.

We made a lot of progress in what is, relatively speaking, a finger snap. With people in energy transition, I point out the EV1 launched in 1996. If we had said 10 years later, “Let’s leave EVs for dead,” that would have been 2006, and there was no EV industry whatsoever. Even if you start with the launch — Tesla’s incorporated in 2003 and 2013, there are basically no EVs in 2013. We have come a really long way in 10 years.

Further to your question from just about a minute ago, the Australian company that I mentioned that’s doing the remarkable work on bioreactors at 20,000 liters, they are actually producing something that’s a cross between duck and foie gras, but it is not duck and it is not foie gras. They are selling it in Singapore and about to sell it in Australia and New Zealand. We’re already at the place where there is at least one company that is thinking outside the box of the current species.

David Roberts

This gets to a whole array of topics that we could talk for a whole other hour on, which is just about the human behavioral parts of all this. This is what’s fascinating to me. If you come up with a novel meat that’s not duck and not foie gras, but some combination, I can imagine, if you’re a rich person in Singapore, that being attractive to you, “Ooh, a novel luxury thing.”

But I can also imagine a yuck reaction. I don’t think I have to imagine it. I think a lot of people just have a yuck reaction. That is a very common sentiment out there in the world. “I’m not eating meat you grew in a lab.” I think a lot of people just have an immediate reaction to it. I wonder, how deep and enduring do you think that instinct is? Do you think that’s something that people are just going to naturally get over with, not that much issue, or do you worry about that gut reaction?

Bruce Friedrich

That is a very natural human reaction to new foods because for the longest time, you figured out whether something was going to kill you by eating it and seeing what happened or make you sick. New foods, we’re programmed to have worries about. The worst polling on cultivated meat still finds more than 20%. If you call it lab-grown meat, if you include a really unattractive photo of it, the worst polling is still more than 20%.

It’s interesting because you say, “If lab-grown meat tastes the same and costs the same, would you switch over a substantial portion of your consumption?” The people who say no, the top two reasons that they say no are they think it’s going to not taste very good, and they explain how it’s going to be mushy or whatever, and they think it’s going to cost too much. They literally just deny the premise of the question.

David Roberts

That shows you how deep those instincts are. People have trouble imagining it genuinely tasting the same.

Bruce Friedrich

Exactly.

David Roberts

Or genuinely costing the same.

Bruce Friedrich

I think once we have hit price and taste parity, whoever the people are who are going to be the holdouts — and there will be some — a lot of that will melt away when they see other people consuming it enthusiastically. Then the benefits kick in. The fact that it’s not going to be contaminated with antibiotics, the fact that bacterial contamination rates are going to be astronomically lower.

If it’s price competitive, taste competitive, for salmon you’re going to be paying a premium to have the mercury and the dioxins in the fish. Feels unlikely that a lot of people are going to continue to do that. What I do think is that you’re going to have the people — the Alice Waters and the Michael Pollans and the people like that —

David Roberts

This is something I wanted to ask too. Right now you’re seeing it out there, this sort of MAHA movement, this bipartisan, grassroots, social reaction against the notion of fakeness and artificiality. There’s a lot of scientific nonsense floating around in that world. Do you view that as a serious threat? This notion that we want something natural and there’s just something unnatural about this and that’s kind of — you can’t argue someone out of that. It’s not really a scientific judgment, it’s just a feeling. Has the MAHA movement yet aligned against this? Do you think it’s going to? Do you worry about that sentiment?

Bruce Friedrich

You hit on it when you said to the degree that it is not rational, and I think a lot of it is not rational, then that would be a very real worry and concern. But I’m not sure that — until the products compete on price and taste, they were not going to take off anyway. The question would be, is MAHA going to be able to hurt scientific or innovation or government support? Not in most of the world.

Interestingly, we just saw an overwhelmingly bipartisan vote in favor of science. NIH’s budget went up. The Department of Energy’s budget went up. NIST’s budget went up. The National Science Foundation, their budget went down from $8.8 to $8.75 billion. But bipartisan support for science seems to be alive and well.

Even in the US I remain cautiously optimistic about the government support that we’ve seen for alternative proteins continuing, especially when you factor in the Chinese competition element. Republicans and Democrats are enthusiastic about alternative proteins.

Even Donald Trump — the first significant grant for cultivated meat R&D since 2005 was the National Science Foundation $3.55 million to UC Davis to set up a cultivated meat consortium. Under the Trump administration, we’ve seen three companies get regulatory approval, which is more than in four years under Joe Biden. Republican concern about things like food self-sufficiency, about economic competitiveness, about keeping pace with China. Then you’ve got the Bipartisan Commission on Biotechnology, which is inclusive of alternative proteins. Knock on wood, it seems like things are going well.

David Roberts

A bunch of research came out a few years ago — I should have this at my fingertips since we’re talking about it, but I’m sure you’re familiar — a big research paper came out a few years ago basically saying the cultivated meat industry is going nowhere. It’s probably not going to go anywhere. It was a big story for a while. I don’t know how that played out. What if that paper and that research was wrong? What was it wrong about? The reason I’m asking this is because my vague memory is that one of the reasons they were skeptical is the extraordinarily high energy input needs of this industry. What happened to all that research? Is that right? What are the energy input considerations here?

Bruce Friedrich

Let me just say on the MAHA thing quickly, the plant-based meat products have lower energy density and more protein, which is one of the key factors that the MAHA health movement is concerned about.

David Roberts

They do love protein.

Bruce Friedrich

Yes. Whatever else you want to think about the protein craze, the plant-based meats, the eight of them that are closest in taste to the animal-based meats — not the jackfruit products or the wheat products or tempeh or whatever, but the Impossible products predominantly. The Impossible hot dog, the Impossible and Beyond burgers, the Impossible nuggets. The Impossible hot dog has three times the protein of a beef hot dog. We have a very strong story to tell on the plant-based side.

On the cultivated side, people right now eat meat despite how it’s produced, not because of how it’s produced. When you start having a conversation about the fact that USDA and FDA have a hundred different chemicals, including things like amoxicillin and penicillin and ractopamine and ivermectin, where there are acceptable levels of contamination in meat — I think they call it, like, generally — no, they don’t call it generally recognized as safe, but that’s basically what it means. When you have the opportunity to have a conversation about current meat production practices and then say what cultivated meat is, is just pure meat and far safer, that feels like a pretty easy conversation to have, to the degree that you’re having a conversation based in rationality.

David Roberts

But are you ever? This is part of what I’ve been doing these last three days — trying to anticipate what crazy — you could never really anticipate in advance, but the idea that we’re just going to have a rational conversation and rationally transition, I’m somewhat skeptical about that, given the experience of the last 10 to 20 years. I’ve just been wondering what craziness could spring up around this. Who knows?

Bruce Friedrich

I could tell stories about enthusiasm in places like Singapore, Japan, Korea, China, Israel. There’s going to be a degree to which the US is not going to want to be left behind. There’s enthusiasm here, too. There’s impressive stuff happening at North Carolina State. There’s a Bezos Center for Sustainable Proteins. Jeff Bezos gave $30 million to three universities through the Bezos Earth Fund, also included alternative proteins in their $100 million AI challenge for nature and climate. $8 million to AI endeavors focused on alternative proteins from the Bezos Earth Fund. UC Davis has a center that’s doing some great work, and Tufts.

David Roberts

Before we leave it behind, let’s talk about the energy input. Am I misremembering — maybe it was vertical farms I’m thinking about — but as I vaguely recall, I thought that the amount of energy input required is a problem here. Is that an issue with cultivated meat?

Bruce Friedrich

When you crunch the climate numbers, you still end up, even with the energy needs — obviously you have far less land required — but for cultivated meat, you do end up with high energy needs. It’s very much a part of electrify everything.

David Roberts

Sure, but I was just saying that this will be another — when we’re talking about electrifying everything, this will be another giant new source of electricity demand if we transition at scale.

Bruce Friedrich

When scientists looked at a pilot plant that was producing 10 million metric tons per year, which is relatively small — I think the average slaughterhouse produces 30, 35 — the energy use needs were high. Most of that was for cooling. The jury is very much out on whether those cooling needs — something like 80% of it was for cooling — are even going to be necessary.

I remember the IEA projections about electrifying transport indicate that a shift to electric vehicles is going to require a lot of energy. It’s a reasonable tradeoff because you get rid of gas. Here you’re looking at things like humanity’s number one source of methane, which over 20 years is 80 times as potent as carbon dioxide. The number one source is ruminant digestion. All of agriculture, it’s over 50%. Similarly, nitrous oxide, 274 times as potent as carbon dioxide. You slash that with a shift to alternative proteins, so you can decarbonize energy.

David Roberts

I’m in no way arguing against it. If you’re going to trade off all that pollution for renewable energy demand, obviously it’s a great trade, but it’s still just worth noting. You’re going to need a lot of renewable energy to run this.

Bruce Friedrich

That is true. There’s also the land use benefits. The alternative is no forests, savannas, no wild spaces at all because everything needs to be taken over by agriculture with all of the massive increases in methane and nitrous oxide that come with that. It definitely is going to profit from energy transition. As I think I heard you say, you can get to abundant energy, you can’t get to abundant land. The amount of land that’s available is what it is.

David Roberts

I just never miss an opportunity to say, no matter what you think about data centers, we need a lot more renewable energy.

Bruce Friedrich

Yes.

David Roberts

In coming years, no matter what. Pick your industry and this is just another one. This is just another one where if you want to make it clean, you need a boatload of renewable energy. Same for cars, same for almost anything. You’re substituting renewable energy for the dirty outputs, but that just means you need a lot of it.

Bruce Friedrich

Plant-based meat uses a lot less energy than producing animal meat because it doesn’t have the same cooling needs for cell growth. If you need fewer factories and you’re producing far fewer inputs, that’s going to be less energy needs overall. But cultivated meat energy needs, assuming that we do have the cooling needs for the production process, is going to be very high. High energy needs, but at a tradeoff of getting rid of what the climate community has thought for a long time was the hard-to-abate sector. What do we do about all that methane? What do we do about all that nitrous oxide?

David Roberts

It turns out the answer to every hard-to-abate sector is just throw a boatload of cheap renewable energy at it and you can solve it.

Bruce Friedrich

Yeah.

David Roberts

But that requires boatloads of renewable energy. As a final thing, next policy steps. It seems like you could address a lot of the current shortcomings of plant-based meats by just mixing in a little real meat.

Bruce Friedrich

Oh yeah.

David Roberts

Selling blends, basically. This is something I think is intuitive to a lot of people. Why isn’t there more of that? Why can’t I buy a pound of ground beef that’s only in reality a half a pound of ground beef and a half a pound of plant simulation? Why isn’t that already on the market? Am I right in saying that that would be a sensible first step to take?

Bruce Friedrich

One of the really great things about that is if you’re blending in mycoprotein or plant protein, you actually have a product that is higher in protein, lower in fat and saturated fat, higher in fiber, lower in cholesterol. It’s a healthier —

David Roberts

A healthier meat.

Bruce Friedrich

Exactly.

David Roberts

You’re selling meat that’s healthier than the other meat.

Bruce Friedrich

You can probably get to price and taste parity maybe right away.

David Roberts

Why is no one doing that?

Bruce Friedrich

I think it is that they are gun-shy from previous efforts where filler, less expensive, less healthy ingredients were shoved into ground beef. At, for example, Taco Bell, I think there was something like this. Maybe at Subway there was the green slime CBS exposé.

David Roberts

Yeah.

Bruce Friedrich

Our pitch to industry is lean in on the health benefits. Consumers felt duped because consumers were duped. We need to be careful on the blends and really need to lean in on the deliciousness and lean in on the health benefits in a way that nobody can claim that this is being hidden from them. In the book, I’m very enthusiastic about the idea of blends and I think it’s a massive opportunity waiting to be picked up.

David Roberts

If I’m just an ordinary person and I’m gripped by the merits of this — meat is having all these awful effects, environmental, social, health. We have now science at hand where we could plausibly substitute products that have just as good taste and texture and umami and satisfaction and that could thereby avoid all these damages of meat. Someone is gripped by this. What should they do? What should they advocate for? What are the policies in the short term? Is it all just science and research or is there some other policy lever that you also think is worth pulling?

Bruce Friedrich

One of the things that I find surprising is just how little analysis has been done of this as an intervention. We’ve got the International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis, their Nature Communications piece. There are overwhelming numbers of climate and environmental scientists, climate and environmental science departments, think tanks for environment and climate, and so too global health, hunger, and development.

There have probably been 10 analyses of alternative proteins and I would guess there have been 100 plus of CDR every year. UNEP releases their report about how we’re going backward on climate. They’ve repeatedly talked about CDR, they’re talking about clean hydrogen, they’re talking about biofuels.

David Roberts

And there’s all this carbon to squeeze out so easily here.

Bruce Friedrich

Exactly.

David Roberts

I think people are gun-shy about the meat. Culturally, people are nervous about it. People have very strong feelings about this.

Bruce Friedrich

A lot of it has to do with the lack of imagination that I talk about in chapter eight. People simply can’t wrap their minds around the idea that something that doesn’t exist now can exist in the future. It’s the same reason that people thought that the dotcom bubble was going to be the end state of interstate commerce and so many other revolutions.

In 1985, the CEO of Apple says home computers are never going to be more than a glorified bookkeeping or something like that. There’s not going to be much of a market for them. There are endless examples of people not believing that a problem can be solved and of thinking that whatever the downsides are of something now, there are always going to be the downsides of that thing. The main thing is we need a lot more people working on this and it’s the sorts of people who are listening to your podcast. We need a lot more reports, we need a lot more analysis, we need a lot more thinking. We also need a lot more science.

David Roberts

When do you think, if you had to put a number on it, I will be able to order a lab-grown hamburger that I will eat and not be able to tell it apart from a regular hamburger just at a local restaurant? How far away is that?

Bruce Friedrich

That is chapter 11 of the book. In the intro I point out that every meat sciences and agriculture department at a university on the planet has a meat lab and 100% of what they’re doing is conventional meat. This is going to be meat in factories. In the same way that every processed food starts in a food lab, but we don’t call it lab-produced cornflakes or whatever.

David Roberts

Lab-grown cornflakes?

Bruce Friedrich

We say cultivated meat, some people say cultured meat, although that sometimes gets people confused because they think it’s packed in salt or something. We say cultivated meat, but I do think lab-grown meat is a misnomer. To answer your question, it really is going to be a function of how much we can create the science that gets us there.

One scenario that I would love to see come to fruition is Microsoft and Google are doing some amazing things with AI and therapeutics. Either of those companies, if they started really going all in on plant-based or cultivated meat, could get us there pretty quickly. I do think China could get us there pretty quickly. Even Korea — I was in Korea six months ago, and they’re really leaning in on food tech and they’re calling it food tech for the world.

David Roberts

Interesting.

Bruce Friedrich